I been watching proceedings at the Republican National Convention in Florida. If you think it's annoying for most liberal Americans, imagine what it's like for us furriners!

Coincidentally, we watched the last episode of The Newsroom a few days ago then decided to re-watch all ten episodes. It's one of the best shows on television. Makes me sad that The West Wing was cancelled. It's not a show that Republicans will enjoy.

Here's the clip from the first episode that sets the tone for a new kind of TV news show. The hero, Will McAvoy, is a cable news anchor who wants to tell it like it is instead of chasing ratings. The excerpt is from a town hall meeting at Northwestern University. A student has just asked why America is the greatest country in the world. (The student shows up again in Episode #10 when she wants to become a "greater fool.")

Friday, August 31, 2012

Creationist "Science Guys" Respond to Bill Nye

The short video by Bill Nye ("The Science Guy") attracted a lot of attention [Bill Nye: Creationism Is Not Appropriate For Children ].

Not to be outdone, Ken Ham and the Creation Museum have taped a response ...

Not to be outdone, Ken Ham and the Creation Museum have taped a response ...

We are [responding to Nye] today with a video rebuttal featuring our “science guys” — Dr. David Menton and Dr. Georgia Purdom of our AiG and Creation Museum staff. These two PhD scientists were asked to reply to Mr. Nye, whose academic credentials do not come close to Drs. Menton and Purdom.I present this for your amusement. I feel a bit sorry for Georgia Purdom since there's a high probability that some of her grandchildren are going to reject creationism. I wonder how she'll deal with that?

How Could We Have Been So Stupid Back in 1976?

Tim Radford reviews The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins [The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins – book review]. The review is a bit late—the book was published in 1976—but I suppose the old adage of "better late than never" applies.

Actually it's not as bizarre as you might think. Lot's of people don't understand the ideas that Dawkins was pushing. He was mostly pointing out that evolution is a phenomenon that takes places at the level of genes and populations. Dawkins tweets that Rafford "gets it" in his review.

Actually it's not as bizarre as you might think. Lot's of people don't understand the ideas that Dawkins was pushing. He was mostly pointing out that evolution is a phenomenon that takes places at the level of genes and populations. Dawkins tweets that Rafford "gets it" in his review.

Lovely retrospective review of The Selfish Gene by Tim Radford, the Guardian's distinguished science writer. He gets it.Read more »

Thursday, August 30, 2012

What Kind of Knowledge Does Philosophy Discover?

Jerry Coyne and I have been thinking along the same lines. We've been reading a lot of books by philosophers and reading their articles and blogs. We're exploring the idea that philosophy and science are different ways of knowing, as the philosophers want us to believe. We've taken to heart the criticism from our philosopher friends that scientists have to understand more about philosophy.

Jerry and I (and many others) have reached the tentative conclusion that much of what passes for modern philosophy is a house of cards. It doesn't tell us anything. It doesn't produce knowledge, or truth.

Read more »

Jerry and I (and many others) have reached the tentative conclusion that much of what passes for modern philosophy is a house of cards. It doesn't tell us anything. It doesn't produce knowledge, or truth.

Read more »

Wednesday, August 29, 2012

Thinking Like an Administrator

A few years ago my university (University of Toronto) decided to take a look at student evaluations. A committee was formed and this was its terms of reference.

If I were in charge of this project I would pick a committee composed almost entirely of the following groups:

I would avoid having any administrators on the committee since the purpose of the committee was to evaluate existing university policy. In general, administrators are reluctant to make radical changes and they have trouble thinking outside the box. Furthermore, most of them don't have time to think seriously about the issue.

Administrators think differently than I do. Here's how they constructed the committee (see Course Evaluation Working Group.

That's what thinking like an administrator looks like.

I don't think my university is unusual. We have thousands of very smart students and teachers but all the important committees seem to be composed of people with heavy administrative responsibilities. Does anyone understand the logic here?

In recognition of the need to periodically revisit practices related to the evaluation of teaching, the Course Evaluation Working Group was formed in the Fall 2009 (Appendix B) and was asked to:This sounds like a good idea. As you know, I am very skeptical about student evaluations [On the Significance of Student Evaluations]. It's abut time that universities took a long hard look at the process with a view to abolishing student evaluations or drastically revising them and reviewing their importance in promotion and tenure decisions. It's even more important to revise the policy on using student evaluations to judge the effectiveness of part-time lecturers and teaching assistants. At the very least, their role in determining teaching awards should be critically examined.

- Review current course evaluation practices across the University of Toronto and at peer institutions;

- Review current research on course evaluation policies and practices;

- If necessary, make recommendations to improve existing policies and practices.

If I were in charge of this project I would pick a committee composed almost entirely of the following groups:

- front-line lecturers in introductory classes, including tenured faculty, untenured faculty, full-time lecturers, and part-time lecturers

- teaching assistants (graduate students)

- undergraduates

I would avoid having any administrators on the committee since the purpose of the committee was to evaluate existing university policy. In general, administrators are reluctant to make radical changes and they have trouble thinking outside the box. Furthermore, most of them don't have time to think seriously about the issue.

Administrators think differently than I do. Here's how they constructed the committee (see Course Evaluation Working Group.

- Edith Hillan (Vice-Provost, Faculty and Academic Life; Co-Chair)

- Jill Matus (Vice-Provost, Students; Co-Chair)

- Grant Allen (Vice-Dean, Undergraduate, Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering)

- Gage Averill (Dean and Vice-Principal, Academic, UTM)

- Cleo Boyd (Director, Robert Gilliespie Academic Skills Centre, UTM)

- Corey Goldman (Associate Chair [Undergraduate], Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, Faculty of Arts & Science)

- Pam Gravestock (Associate Director, Centre for Teaching Support & Innovation)

- Emily Greenleaf (Faculty Liaison & Research Associate, Centre for Teaching Support & Innovation)

- Jodi Herold-McIlroy (Wilson Centre, Faculty of Medicine)

- Glen Jones (Associate Dean, Academic, OISE) Helen Lasthiotakis (Director of Academic Programs and Policy)

- Marden Paul (Director, Planning, Governance & Assessment)

- Cheryl Regehr (Vice-Provost, Academic Programs)

- Carol Rolheiser (Director, Centre for Teaching Support & Innovation)

- Jay Rosenfield (Vice-Dean, Undergraduate Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine)

- John Scherk (Vice-Dean, UTSC)

- Elizabeth Smyth (Vice-Dean, Programs, School of Graduate Studies)

- Suzanne Stevenson (Vice-Dean, Teaching & Learning, Faculty of Arts & Science)

That's what thinking like an administrator looks like.

I don't think my university is unusual. We have thousands of very smart students and teachers but all the important committees seem to be composed of people with heavy administrative responsibilities. Does anyone understand the logic here?

Tuesday, August 28, 2012

More Creationist Objections to Unguided Evolution

Maybe it's just my imagination, but I think I detect a change on Evolution News & View and on Uncommon Descent. For years these blogs have been attacking evolution without paying the least attention to what their opponents are saying. Lately, however, there seem to be some authors who are actually listening to their opponents and trying to address the main criticisms of the IDiot position.

Sometimes you even see articles that are close to being scientifically correct and I've even seen articles that recognize the existence of modern evolutionary theory (i.e. not Darwinism).

The good articles are still quite rare but I'm encouraged by the fact that they are listening.

The latest contribution is by Stephen A. Batzer, a contributor to Evolution News & Views since May 10, 2012. Batzer has a Ph.D. in Mechanical Engineering (see The Salem Conjecture). He's responding to an earlier post of mine where I attempted to explain to Casey Luskin why he was wrong about evolutionary theory [Is "Unguided" Part of Modern Evolutionary Theory?]. Recall that Luskin was saying that the "unguided" nature of evolution was a core part of the theory of Darwinian evolution.

Read more »

Sometimes you even see articles that are close to being scientifically correct and I've even seen articles that recognize the existence of modern evolutionary theory (i.e. not Darwinism).

The good articles are still quite rare but I'm encouraged by the fact that they are listening.

The latest contribution is by Stephen A. Batzer, a contributor to Evolution News & Views since May 10, 2012. Batzer has a Ph.D. in Mechanical Engineering (see The Salem Conjecture). He's responding to an earlier post of mine where I attempted to explain to Casey Luskin why he was wrong about evolutionary theory [Is "Unguided" Part of Modern Evolutionary Theory?]. Recall that Luskin was saying that the "unguided" nature of evolution was a core part of the theory of Darwinian evolution.

Read more »

The Flying Spaghetti Monster Steals Meatballs (What's the Purpose of Philosophy?)

The Flying Spaghetti Monster is all-powerful and all-knowing and she loves meatballs. She is also very sneaky and doesn't want to leave any evidence of her existence. That's why she's very careful to only steal meatballs that won't be missed. (How often do you count the meatballs in your spaghetti?).

As far as I know this is a perfectly valid philosophical argument. If you accept the premises then it's quite possible that meatballs are disappearing from kitchens and restaurants without us ever being aware of the problem.

I'm not a philosopher but I strongly suspect that there aren't any papers on the possible existence of the Flying Spaghetti Monster in the philosophical literature. I doubt that there are any Ph.D. theses on the topic.

Read more »

As far as I know this is a perfectly valid philosophical argument. If you accept the premises then it's quite possible that meatballs are disappearing from kitchens and restaurants without us ever being aware of the problem.

I'm not a philosopher but I strongly suspect that there aren't any papers on the possible existence of the Flying Spaghetti Monster in the philosophical literature. I doubt that there are any Ph.D. theses on the topic.

Read more »

Monday, August 27, 2012

Monday's Molecule #183

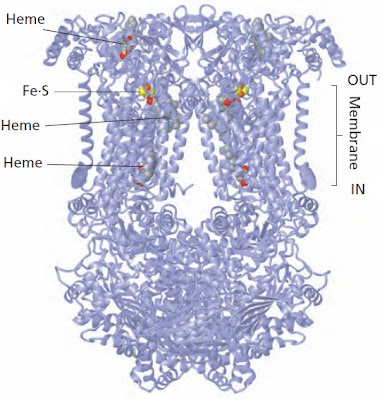

Last week's molecule was a small protein machine that pumps protons across a membrane (ubiquinol:cytochrome c oxidoreductase) [Monday's Molecule #182]. The winner was Stephen Spiro. I think he's a student at the University of Toronto (UT) but it's a campus I haven't heard of in a place called "Dallas."

This week's molecule is a lot less complicated although it's rather strange looking. This molecule has a very specific use. Name the molecule—the common name will do—and describe its use.

Post your answers as a comment. I'll hold off releasing any comments for 24 hours. The first one with the correct answer wins. I will only post mostly correct answers to avoid embarrassment. The winner will be treated to a free lunch.

There could be two winners. If the first correct answer isn't from an undergraduate student then I'll select a second winner from those undergraduates who post the correct answer. You will need to identify yourself as an undergraduate in order to win. (Put "undergraduate" at the bottom of your comment.)

Some past winners are from distant lands so their chances of taking up my offer of a free lunch are slim. (That's why I can afford to do this!)

In order to win you must post your correct name. Anonymous and pseudoanonymous commenters can't win the free lunch.

Winners will have to contact me by email to arrange a lunch date. Please try and beat the regular winners. Most of them live far away and I'll never get to take them to lunch. This makes me sad.

Comments are invisible for 24 hours. Comments are now open.

UPDATE: The molecule is raltitrexed, also known as Tomudex. It's an inhibitor of the enzyme thymidylate synthase, the enzyme responsible for converting dUMP to dTMP. The drug is effective as an anti-cancer agent since it prevents cell division by blocking DNA synthesis. The winner is Raul A. Félix de Sousa (again).

Winners

Nov. 2009: Jason Oakley, Alex Ling

Oct. 17: Bill Chaney, Roger Fan

Oct. 24: DK

Oct. 31: Joseph C. Somody

Nov. 7: Jason Oakley

Nov. 15: Thomas Ferraro, Vipulan Vigneswaran

Nov. 21: Vipulan Vigneswaran (honorary mention to Raul A. Félix de Sousa)

Nov. 28: Philip Rodger

Dec. 5: 凌嘉誠 (Alex Ling)

Dec. 12: Bill Chaney

Dec. 19: Joseph C. Somody

Jan. 9: Dima Klenchin

Jan. 23: David Schuller

Jan. 30: Peter Monaghan

Feb. 7: Thomas Ferraro, Charles Motraghi

Feb. 13: Joseph C. Somody

March 5: Albi Celaj

March 12: Bill Chaney, Raul A. Félix de Sousa

March 19: no winner

March 26: John Runnels, Raul A. Félix de Sousa

April 2: Sean Ridout

April 9: no winner

April 16: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

April 23: Dima Klenchin, Deena Allan

April 30: Sean Ridout

May 7: Matt McFarlane

May 14: no winner

May 21: no winner

May 29: Mike Hamilton, Dmitri Tchigvintsev

June 4: Bill Chaney, Matt McFarlane

June 18: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

June 25: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 2: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 16: Sean Ridout, William Grecia

July 23: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 30: Bill Chaney and Raul A. Félix de Sousa

Aug. 7: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

Aug. 13: Matt McFarlane

Aug. 20: Stephen Spiro

Aug. 27: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

This week's molecule is a lot less complicated although it's rather strange looking. This molecule has a very specific use. Name the molecule—the common name will do—and describe its use.

Post your answers as a comment. I'll hold off releasing any comments for 24 hours. The first one with the correct answer wins. I will only post mostly correct answers to avoid embarrassment. The winner will be treated to a free lunch.

There could be two winners. If the first correct answer isn't from an undergraduate student then I'll select a second winner from those undergraduates who post the correct answer. You will need to identify yourself as an undergraduate in order to win. (Put "undergraduate" at the bottom of your comment.)

Some past winners are from distant lands so their chances of taking up my offer of a free lunch are slim. (That's why I can afford to do this!)

In order to win you must post your correct name. Anonymous and pseudoanonymous commenters can't win the free lunch.

Winners will have to contact me by email to arrange a lunch date. Please try and beat the regular winners. Most of them live far away and I'll never get to take them to lunch. This makes me sad.

UPDATE: The molecule is raltitrexed, also known as Tomudex. It's an inhibitor of the enzyme thymidylate synthase, the enzyme responsible for converting dUMP to dTMP. The drug is effective as an anti-cancer agent since it prevents cell division by blocking DNA synthesis. The winner is Raul A. Félix de Sousa (again).

Winners

Nov. 2009: Jason Oakley, Alex Ling

Oct. 17: Bill Chaney, Roger Fan

Oct. 24: DK

Oct. 31: Joseph C. Somody

Nov. 7: Jason Oakley

Nov. 15: Thomas Ferraro, Vipulan Vigneswaran

Nov. 21: Vipulan Vigneswaran (honorary mention to Raul A. Félix de Sousa)

Nov. 28: Philip Rodger

Dec. 5: 凌嘉誠 (Alex Ling)

Dec. 12: Bill Chaney

Dec. 19: Joseph C. Somody

Jan. 9: Dima Klenchin

Jan. 23: David Schuller

Jan. 30: Peter Monaghan

Feb. 7: Thomas Ferraro, Charles Motraghi

Feb. 13: Joseph C. Somody

March 5: Albi Celaj

March 12: Bill Chaney, Raul A. Félix de Sousa

March 19: no winner

March 26: John Runnels, Raul A. Félix de Sousa

April 2: Sean Ridout

April 9: no winner

April 16: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

April 23: Dima Klenchin, Deena Allan

April 30: Sean Ridout

May 7: Matt McFarlane

May 14: no winner

May 21: no winner

May 29: Mike Hamilton, Dmitri Tchigvintsev

June 4: Bill Chaney, Matt McFarlane

June 18: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

June 25: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 2: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 16: Sean Ridout, William Grecia

July 23: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 30: Bill Chaney and Raul A. Félix de Sousa

Aug. 7: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

Aug. 13: Matt McFarlane

Aug. 20: Stephen Spiro

Aug. 27: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

The Ethics of Genome Analysis

Lots of people are having their genomes sequenced or otherwise analyzed for specific alleles. Those people should get all the information that comes out of the analyses although, hopefully, it will be scientifically correct information and any medical relevance will be explained by experts.1

There's another group of people who submit their genomes for research purposes only and they usually sign consent forms indicating that their name will not be associated with the results. Under those circumstances, the researchers should never have access to the individual's name or any circumstances that are not relevant to the study.

Apparently that simple ethical rule is not always standard practice. Gina Kolatea writes about some ethical issues in the New York Times: Genes Now Tell Doctors Secrets They Can’t Utter.

Here's an example from her article ...

Most of the "ethical problems" in the article are of this type. They involve researchers who are supposed to be concentrating on research and not on the treatment of individual patients. Those researchers have no idea whether the patients already know which alleles they carry or whether they are already undergoing medical treatment. That's just as it should be. If a DNA donor doesn't want to be contacted then it's ethically wrong for the researchers to violate that contract no matter how justified they think they are being. Furthermore, it should be impossible for them to find out the name and address of the donor so the issue should never come up.

John Hawks thinks this is an interesting ethical problem and he wants his students to discuss it in his classes [Grasping the genomic palantir].

There's another group of people who submit their genomes for research purposes only and they usually sign consent forms indicating that their name will not be associated with the results. Under those circumstances, the researchers should never have access to the individual's name or any circumstances that are not relevant to the study.

Apparently that simple ethical rule is not always standard practice. Gina Kolatea writes about some ethical issues in the New York Times: Genes Now Tell Doctors Secrets They Can’t Utter.

Here's an example from her article ...

One of the first cases came a decade ago, just as the new age of genetics was beginning. A young woman with a strong family history of breast and ovarian cancer enrolled in a study trying to find cancer genes that, when mutated, greatly increase the risk of breast cancer. But the woman, terrified by her family history, also intended to have her breasts removed prophylactically.This is a rather simple case of the researchers violating a standard protocol. They should not have known the identity of the patient and they should not have known what she intended to do.

Her consent form said she would not be contacted by the researchers. Consent forms are typically written this way because the purpose of such studies is not to provide medical care but to gain new insights. The researchers are not the patients’ doctors.

But in this case, the researchers happened to know about the woman’s plan, and they also knew that their study indicated that she did not have her family’s breast cancer gene. They were horrified.

Most of the "ethical problems" in the article are of this type. They involve researchers who are supposed to be concentrating on research and not on the treatment of individual patients. Those researchers have no idea whether the patients already know which alleles they carry or whether they are already undergoing medical treatment. That's just as it should be. If a DNA donor doesn't want to be contacted then it's ethically wrong for the researchers to violate that contract no matter how justified they think they are being. Furthermore, it should be impossible for them to find out the name and address of the donor so the issue should never come up.

John Hawks thinks this is an interesting ethical problem and he wants his students to discuss it in his classes [Grasping the genomic palantir].

That case is ethically straightforward compared to others, because the researchers could make a difference to an immediate medical decision. On the other hand, how many risk-free research participants went ahead with prophylactic mastectomies because researchers didn't know about their plans?What will students learn from discussing issues like these? What controls are in place to make sure that students are informed about all the ethical issues? Will they be told that standard scientific protocols were violated once the researchers knew what the patient intended to do?

I think the article will be a good one for prompting student discussions in my courses, and I'll likely assign it widely. But I think the central ethical problem discussed in the article is temporary.

1. "Experts" do NOT include employees of any for-profit company that took money for sequencing the genome.

Thinking Critically About Graphs

Jeff Mahr is trying to teach his students how to think critically so he asked them a question about a graph. Check it out to see if you would pass his course: Clearly Critical Thinking?.

Wednesday, August 22, 2012

For All Those People Who Like to Take Pictures of Their Food Using Their iPhone

You know who you are!

Tomoko Ohta and Nearly Neutral Theory

There's an interview with Tomoko Ohta in the August 21, 2012 issue of Current Biology: Tomoko Ohta.

You should know who she is but in case you don't, here's part of the brief bio ...

She describes what happened when she joined Kimura's group at Tokyo.

It's a shame there's no Nobel Prize for evolution.

You should know who she is but in case you don't, here's part of the brief bio ...

In 1973, she presented her first major paper entitled ‘Slightly deleterious mutant substitutions in evolution’. This theory was an expansion of Kimura's ‘neutral theory’, which Ohta called the ‘nearly neutral theory’ of molecular evolution. Her theory emphasizes the importance of interaction of drift and weak selection, and hence the role of slightly deleterious mutations in molecular evolution. With the accumulation of genome data, some of the predictions of the nearly neutral theory have been verified. The theory also provides a mechanism for the evolution of complex systems. Her other subject is to clarify the mechanisms of evolution and variation of multigene families. She has received several honors, including the foreign membership of the National Academy of Sciences, USA and Person of Cultural Merit, Japan.It's very important to understand the essence of Nearly Neutral Theory since it explains the relationship between fitness and population size. Everyone needs to understand that Ohta demonstrated how slightly deleterious alleles can be fixed in a population. Her work showed that an allele can become effectively neutral in small populations even though it may actually lower the fitness of an individual. It's a way of explaining the limits of natural selection and of extending the Neutral Theory of Kimura.

She describes what happened when she joined Kimura's group at Tokyo.

At that time, Kimura was thinking of combining the theory of stochastic population genetics, the field he had been working on, with biochemical data on the nature of the genetic material. He proposed his now famous ‘neutral theory of molecular evolution’ in 1968. The ‘neutral theory’ proposed that most evolutionary changes at the molecular level were caused by random genetic drift rather than by natural selection. Note that the neutral theory classifies new mutations as deleterious, neutral, and advantageous. Under this classification, the rate of mutant substitutions in evolution can be formulated by the stochastic theory of population genetics. Kimura's theory was simple and elegant, yet I was not quite satisfied with it, because I thought that natural selection was not as simple as the mutant classification the neutral theory indicated, and that there would be border-line mutations with very small effects between the classes. I thus went ahead and proposed the nearly neutral theory of molecular evolution in 1973. The theory was not simple, and much more complicated, but to me, more realistic, and I have been working on this problem ever since.This has nothing to do with Darwinism even though it's a fundamental part of modern evolutionary theory. You can't have an intelligent discussion about genome evolution, adaptationism, molecular evolution, or junk DNA without a firm grasp of Nearly Neutral Theory.

It's a shame there's no Nobel Prize for evolution.

Tuesday, August 21, 2012

Designing a New Biochemistry Curriculum

I want to draw your attention to an article in the July/August 2012 issue of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education (BAMBED). The authors are Michael Klymkowski and Melanie Cooper and the title is "Now for the Hard Part: The Path to Curricular Design."

In the long run, it really doesn't matter whether you are employing the very latest pedagogical techniques if what you are teaching is crap.

But we also need to recognize that there's a relationship between what we teach and how we teach it. If you want to teach scientific thinking—as opposed to memorizing pathways—then there may be superior ways to do it.

There is a growing acknowledgement that STEM education, at all levels, is not producing learners with a deep understanding of core disciplinary concepts [1]. A number of efforts in STEM education reform have focused on the development of ‘‘student-centered’’ active learning environments, which, while believed to be more effective, have yet to be widely adopted [2]. What has not been nearly as carefully considered, however, is the role of the curriculum itself as perhaps the most persistent obstacle to effective science education. It is now time to examine not only how we teach, but also what we teach and how it affects student learning.This is an important point. Most of the science education reforms that are being proposed these days focus on style rather than substance.

In the long run, it really doesn't matter whether you are employing the very latest pedagogical techniques if what you are teaching is crap.

But we also need to recognize that there's a relationship between what we teach and how we teach it. If you want to teach scientific thinking—as opposed to memorizing pathways—then there may be superior ways to do it.

Recognizing how challenging it is to build scientific understanding requires that we recognize that scientific thinking, in and of itself, is by no means easy and is certainly not ‘‘natural.’’ We are programmed by survival based and eminently practical evolutionary processes to ‘‘think fast’’ [8]. In contrast, scientific thinking is slow, hard, and difficult to maintain. If students are not exposed to environments where they must practice and use the skills (both metacognitive and procedural) that they need to learn, they may fall back on fast, surface level answers, and fail to recognize what it is that they do not understand.Scientific thinking (and critical thinking) have to be experienced and practiced. That means you have to make time for that in your course.

Klymkowsky, M.W. and Cooper, M.M. (2012) Now for the hard part: The path to coherent curricular design. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education 40:271–272. [doi: 10.1002/bmb.20614]

Origin Stories

Here's a podcast on the origin of life. Check out the website to see who's talking [Origin Stories].

For some strange reason the show begins with Greek mythology. Then it moves on to real science. There are three origin of life scenarios ...

The second half of the show features soundbites suggesting that the origin of complex organic molecules on Earth is a problem but they could form in interstellar space. But this is exactly the "problem" that Metabolism First tries to explain so it's puzzling that there was no advocate of this view on the show.

This is a complicated topic that is not compatible with the format of this show. How do you, dear readers, think it rates as science journalism? Is this a good way to get the general public interested in science?

The blurb on the website suggests that the series is highly rated by fellow journalists.

For some strange reason the show begins with Greek mythology. Then it moves on to real science. There are three origin of life scenarios ...

- Darwin's warm little pond ... equivalent to primordial soup.

- Panspermia ... which doesn't solve anything.

- Hydrothermal vents ... which aren't explained

The second half of the show features soundbites suggesting that the origin of complex organic molecules on Earth is a problem but they could form in interstellar space. But this is exactly the "problem" that Metabolism First tries to explain so it's puzzling that there was no advocate of this view on the show.

This is a complicated topic that is not compatible with the format of this show. How do you, dear readers, think it rates as science journalism? Is this a good way to get the general public interested in science?

The blurb on the website suggests that the series is highly rated by fellow journalists.

A show that explores the bigger questions. Winner of "Top New Artists" and "Most Licensed by Public Radio Remix" awards at PRX's 2011 Zeitfunk Awards.

Monday, August 20, 2012

Pseudogenes Are Pseudogenes and They Are Almost Always Junk

The IDiots have found a paper by Wen et al. (2012) with a very provocative title, "Pseudogenes are not pseudo any more."

Naturally, lawyer Casey Luskin is all over this: Paper Rebuffs Assumption that Pseudogenes Are Genetic "Junk," Claims Function Is "Widespread". And just as naturally, the folks at Uncommon Descent (probably lawyer Barry Arrington) jump on the bandwagon: Junk DNA: Yes, paper admits, it WAS thought to be junk.

The authors of the paper, including Templeton Prize winner Francisco J Ayala, claim that pseduogenes exhibit two puzzling properties: (a) similar processed pseudogenes occur in mouse and humans suggesting that they are conserved, and (b) many pseudogenes are transcribed.

Processed pseudogenes arise when mRNA transcripts are reverse transcribed and inserted back into the genome. They usually come from genes that are highly expressed in germ line cells. Such genes tend to be highly conserved in related species. Mammals are closely related on the scale that were talking about. It's not surprising that a few new pseudogenes in such lineages are very similar in sequence. They're still pseudogenes. The vast majority of known pseudogenes are evolving at a rate that approximates the rate of mutation indicating that they are not constrained by negative selection.

Many pseudogenes are derived from gene duplications followed by mutations in one of the copies that make them incapable of producing a functional product. There's no reason to suspect that the first of these debilitating mutations will prevent transcription; therefore, one expects that many pseudogenes will be transcribed.

Some pseudogenes have been co-opted to provide a different function. There aren't very many examples but that doesn't stop the IDiots from making the fantastic leap from 0.0001% to 100%. (Pseudogenes represent about 1% of the genome [What's in Your Genome? ] so even if we assume that every single pseudogene is not a pseudogene, it hardly makes a dint in the amount of junk DNA.)

I discussed all this when I reviewed Jonathan Well's book The Myth of Junk DNA. The relevant chapter is Chapter 5 [Junk & Jonathan: Part 8—Chapter 5]. That review was posted in May 2011. It seems clear that the lawyers on the IDiot websites haven't read it.

Here's what one of them says on Uncommon Descent.

Naturally, lawyer Casey Luskin is all over this: Paper Rebuffs Assumption that Pseudogenes Are Genetic "Junk," Claims Function Is "Widespread". And just as naturally, the folks at Uncommon Descent (probably lawyer Barry Arrington) jump on the bandwagon: Junk DNA: Yes, paper admits, it WAS thought to be junk.

The authors of the paper, including Templeton Prize winner Francisco J Ayala, claim that pseduogenes exhibit two puzzling properties: (a) similar processed pseudogenes occur in mouse and humans suggesting that they are conserved, and (b) many pseudogenes are transcribed.

Processed pseudogenes arise when mRNA transcripts are reverse transcribed and inserted back into the genome. They usually come from genes that are highly expressed in germ line cells. Such genes tend to be highly conserved in related species. Mammals are closely related on the scale that were talking about. It's not surprising that a few new pseudogenes in such lineages are very similar in sequence. They're still pseudogenes. The vast majority of known pseudogenes are evolving at a rate that approximates the rate of mutation indicating that they are not constrained by negative selection.

Many pseudogenes are derived from gene duplications followed by mutations in one of the copies that make them incapable of producing a functional product. There's no reason to suspect that the first of these debilitating mutations will prevent transcription; therefore, one expects that many pseudogenes will be transcribed.

Some pseudogenes have been co-opted to provide a different function. There aren't very many examples but that doesn't stop the IDiots from making the fantastic leap from 0.0001% to 100%. (Pseudogenes represent about 1% of the genome [What's in Your Genome? ] so even if we assume that every single pseudogene is not a pseudogene, it hardly makes a dint in the amount of junk DNA.)

I discussed all this when I reviewed Jonathan Well's book The Myth of Junk DNA. The relevant chapter is Chapter 5 [Junk & Jonathan: Part 8—Chapter 5]. That review was posted in May 2011. It seems clear that the lawyers on the IDiot websites haven't read it.

Here's what one of them says on Uncommon Descent.

Darwin’s followers considered junk DNA powerful evidence for their theory, which is really a philosophy (often a cult), and that they often expressed that view, often triumphantly. Others insist it is true anyway.I'm not even going to bother pointing out how stupid that is. If you're reading Sandwalk, chances are high that you could detect the lies1 with your eyes closed.

The problem they hope to suppress is that if lots of junk in our DNA is such powerful evidence for their theory, then little junk throws it into doubt. That is, if it is such a good theory, why was it wrong on a point that was announced so triumphantly?

So it is a good thing that the science-minded public is reminded of the historical fact that Darwinism was supported by junk DNA. And it will be fun when the squirming editorials come out in science mags, warning people not to read too much into this, Darwin is still right.

1. Yes, "lies." At this point there's no other explanation.

Wen, Y-Z., Zheng, L-L., Qu, L-H., Ayala, F.J., and Lun, Z-R. (2012) Pseudogenes are not pseudo any more. RNA Biology 9: 27 - 32. [doi: 10.4161/rna.9.1.18277]

Monday's Molecule #182

Last week's molecule was a ganglioside (GM2) that's associated with Tay-Sachs disease [Monday's Molecule #181].

This week's molecule is one of the most important enzymes in the known universe. What is it?

Post your answers as a comment. I'll hold off releasing any comments for 24 hours. The first one with the correct answer wins. I will only post mostly correct answers to avoid embarrassment. The winner will be treated to a free lunch.

There could be two winners. If the first correct answer isn't from an undergraduate student then I'll select a second winner from those undergraduates who post the correct answer. You will need to identify yourself as an undergraduate in order to win. (Put "undergraduate" at the bottom of your comment.)

Some past winners are from distant lands so their chances of taking up my offer of a free lunch are slim. (That's why I can afford to do this!)

In order to win you must post your correct name. Anonymous and pseudoanonymous commenters can't win the free lunch.

Winners will have to contact me by email to arrange a lunch date. Please try and beat the regular winners. Most of them live far away and I'll never get to take them to lunch. This makes me sad.

Comments are invisible for 24 hours. Comments are now open.

UPDATE: The molecule is complex III or ubiquinol:cytochrome c oxidoreductase, the enzyme responsible for the Q-cycle and the transport of proton across the plasma membrane of bacteria and the inner mitochondrial membrane in eukaryotes. This week's winner is Stephen Spiro.

Winners

Nov. 2009: Jason Oakley, Alex Ling

Oct. 17: Bill Chaney, Roger Fan

Oct. 24: DK

Oct. 31: Joseph C. Somody

Nov. 7: Jason Oakley

Nov. 15: Thomas Ferraro, Vipulan Vigneswaran

Nov. 21: Vipulan Vigneswaran (honorary mention to Raul A. Félix de Sousa)

Nov. 28: Philip Rodger

Dec. 5: 凌嘉誠 (Alex Ling)

Dec. 12: Bill Chaney

Dec. 19: Joseph C. Somody

Jan. 9: Dima Klenchin

Jan. 23: David Schuller

Jan. 30: Peter Monaghan

Feb. 7: Thomas Ferraro, Charles Motraghi

Feb. 13: Joseph C. Somody

March 5: Albi Celaj

March 12: Bill Chaney, Raul A. Félix de Sousa

March 19: no winner

March 26: John Runnels, Raul A. Félix de Sousa

April 2: Sean Ridout

April 9: no winner

April 16: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

April 23: Dima Klenchin, Deena Allan

April 30: Sean Ridout

May 7: Matt McFarlane

May 14: no winner

May 21: no winner

May 29: Mike Hamilton, Dmitri Tchigvintsev

June 4: Bill Chaney, Matt McFarlane

June 18: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

June 25: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 2: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 16: Sean Ridout, William Grecia

July 23: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 30: Bill Chaney and Raul A. Félix de Sousa

Aug. 7: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

Aug. 13: Matt McFarlane

Aug. 20: Stephen Spiro

This week's molecule is one of the most important enzymes in the known universe. What is it?

Post your answers as a comment. I'll hold off releasing any comments for 24 hours. The first one with the correct answer wins. I will only post mostly correct answers to avoid embarrassment. The winner will be treated to a free lunch.

There could be two winners. If the first correct answer isn't from an undergraduate student then I'll select a second winner from those undergraduates who post the correct answer. You will need to identify yourself as an undergraduate in order to win. (Put "undergraduate" at the bottom of your comment.)

Some past winners are from distant lands so their chances of taking up my offer of a free lunch are slim. (That's why I can afford to do this!)

In order to win you must post your correct name. Anonymous and pseudoanonymous commenters can't win the free lunch.

Winners will have to contact me by email to arrange a lunch date. Please try and beat the regular winners. Most of them live far away and I'll never get to take them to lunch. This makes me sad.

UPDATE: The molecule is complex III or ubiquinol:cytochrome c oxidoreductase, the enzyme responsible for the Q-cycle and the transport of proton across the plasma membrane of bacteria and the inner mitochondrial membrane in eukaryotes. This week's winner is Stephen Spiro.

Winners

Nov. 2009: Jason Oakley, Alex Ling

Oct. 17: Bill Chaney, Roger Fan

Oct. 24: DK

Oct. 31: Joseph C. Somody

Nov. 7: Jason Oakley

Nov. 15: Thomas Ferraro, Vipulan Vigneswaran

Nov. 21: Vipulan Vigneswaran (honorary mention to Raul A. Félix de Sousa)

Nov. 28: Philip Rodger

Dec. 5: 凌嘉誠 (Alex Ling)

Dec. 12: Bill Chaney

Dec. 19: Joseph C. Somody

Jan. 9: Dima Klenchin

Jan. 23: David Schuller

Jan. 30: Peter Monaghan

Feb. 7: Thomas Ferraro, Charles Motraghi

Feb. 13: Joseph C. Somody

March 5: Albi Celaj

March 12: Bill Chaney, Raul A. Félix de Sousa

March 19: no winner

March 26: John Runnels, Raul A. Félix de Sousa

April 2: Sean Ridout

April 9: no winner

April 16: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

April 23: Dima Klenchin, Deena Allan

April 30: Sean Ridout

May 7: Matt McFarlane

May 14: no winner

May 21: no winner

May 29: Mike Hamilton, Dmitri Tchigvintsev

June 4: Bill Chaney, Matt McFarlane

June 18: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

June 25: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 2: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 16: Sean Ridout, William Grecia

July 23: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 30: Bill Chaney and Raul A. Félix de Sousa

Aug. 7: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

Aug. 13: Matt McFarlane

Aug. 20: Stephen Spiro

Sunday, August 19, 2012

Green T4 Bacteriophage Earrings

Ms. Sandwalk's birthday is coming up in a few weeks and I'm getting nervous. I always seem to choose the wrong present. Turns out that a telephoto lens for her camera isn't very romantic. Who knew?

This year it's a sure thing. I worked on bacteriophage T4 as a graduate student and she helped me type my thesis. It's the perfect gift. [NEW - Green T4 Bacteriophage Earrings]

Right?

This year it's a sure thing. I worked on bacteriophage T4 as a graduate student and she helped me type my thesis. It's the perfect gift. [NEW - Green T4 Bacteriophage Earrings]

Right?

A Question for Anthropologists

This year's special issue of Scientific American is "Beyond the Limits of Science." One of the articles is about human evolution. The title is Super Humanity in the print issue but the online title is Aspiration Makes Us Human.

The author is Robert M. Sapolsky, a professor of biology and neurology at Stanford University in California (USA). Stanford is a pretty good school so he probably knows his stuff.

Here's how Sapolsky starts off ...

Let's assume that our ancestors left Africa only 50,000 years ago. If that represents 1% of our evolutionary history then it means that our species and it's immediate direct ancestors lived on the African open savannah for 4,950,000 years.

Could that possibly be true even if you only count the main line of descent? What is the evidence that supports these claims? How much of the early history of Homo sapiens was influenced by adaptation to open savannah? Does anyone have a scientific answer to this question?

Setting aside the "main line," we now have good evidence that modern Homo sapiens acquired alleles from Neanderthals, Denisovans, and, perhaps more ancient Homo erectus. All three spent substantial time evolving in places that looked nothing like the open savannah in Africa. The proportion of the "invading" alleles may be only 10% or less but that's still significant.

Do we know for sure that all of the important features of modern humans came from alleles that were fixed by adaptation on the savannah? What if some of the more important behavioral alleles came from Neanderthals and became fixed because they were so much fitter than the savannah alleles?

Take the alleles that make women like to shop, for example. Maybe they arose in the Denisovans because they have access to better trade routes in central China? Maybe the women on the savannah preferred to store their cash in elephant tusks?

The evolutionary psychologists have developed awesome explanations for human behavior based on their detailed understanding of the social structure of hunter-gatherer groups living on the savannah for millions of years. What if our genetic ancestors lived elsewhere? The bad news is that all those just-so stories will be wrong. The good news is that they can publish a completely different set of stories and get twice as many publications.

The author is Robert M. Sapolsky, a professor of biology and neurology at Stanford University in California (USA). Stanford is a pretty good school so he probably knows his stuff.

Here's how Sapolsky starts off ...

Sit down with an anthropologist to talk about the nature of humans, and you are likely to hear this chestnut: “Well, you have to remember that 99 percent of human history was spent on the open savanna in small hunter-gatherer bands.” It's a classic cliché of science, and it's true. Indeed, those millions of ancestral years produced many of our hallmark traits—upright walking and big brains, for instance.This doesn't make sense.

Let's assume that our ancestors left Africa only 50,000 years ago. If that represents 1% of our evolutionary history then it means that our species and it's immediate direct ancestors lived on the African open savannah for 4,950,000 years.

Could that possibly be true even if you only count the main line of descent? What is the evidence that supports these claims? How much of the early history of Homo sapiens was influenced by adaptation to open savannah? Does anyone have a scientific answer to this question?

Setting aside the "main line," we now have good evidence that modern Homo sapiens acquired alleles from Neanderthals, Denisovans, and, perhaps more ancient Homo erectus. All three spent substantial time evolving in places that looked nothing like the open savannah in Africa. The proportion of the "invading" alleles may be only 10% or less but that's still significant.

Do we know for sure that all of the important features of modern humans came from alleles that were fixed by adaptation on the savannah? What if some of the more important behavioral alleles came from Neanderthals and became fixed because they were so much fitter than the savannah alleles?

Take the alleles that make women like to shop, for example. Maybe they arose in the Denisovans because they have access to better trade routes in central China? Maybe the women on the savannah preferred to store their cash in elephant tusks?

The evolutionary psychologists have developed awesome explanations for human behavior based on their detailed understanding of the social structure of hunter-gatherer groups living on the savannah for millions of years. What if our genetic ancestors lived elsewhere? The bad news is that all those just-so stories will be wrong. The good news is that they can publish a completely different set of stories and get twice as many publications.

Saturday, August 18, 2012

Atheists Have to Address the Social and Emotional Needs of People (or the Church Wins)

I stole this title from the Friendly Atheist, Hemant Mehta [Atheists Have to Address the Social and Emotional Needs of People (or the Church Wins)].

Watch the video. Hemant makes the point that large churches in the USA provide a number of social services that, apparently, aren't available anywhere else. He points out that asking someone to give up their religion is asking them to give up all kinds of other things like volunteer groups, daycare, and support groups. Hemant thinks that atheists need to create "churches" that will fill these needs.

This is the same argument made by another prominent American atheist, Dan Dennett [What Should Replace Religion?].

I don't get it. Why should atheists have to form their own "churches"? In Canada these services are provided by local community centres—there are four within a short drive of were I live. The one within walking distance is called South Common Community Centre. It has a swimming pool (see photo above), a public library, many gyms and exercise rooms, and meeting rooms. There's daycare and classes of various sorts, dozens of volunteer organizations and support groups, swimming lessons for adults and children and lots more. The community centres are funded by civic government and paid for by taxes. They are open to everybody.

Some of them rent out space for church services on Sundays but they are definitely secular. They are not atheist centres.

The best way to provide the services that people need has already been invented. It's called socialism. It's wrong to assume that the only solution is competing services supplied by various religious churches plus one non-religious church.

Is it impossible to work in America toward the goal of secular social services for all? Is that why the only solution seems to be for atheists/humanists to form their own competing religion to provide those services for nonbelievers?

Watch the video. Hemant makes the point that large churches in the USA provide a number of social services that, apparently, aren't available anywhere else. He points out that asking someone to give up their religion is asking them to give up all kinds of other things like volunteer groups, daycare, and support groups. Hemant thinks that atheists need to create "churches" that will fill these needs.

This is the same argument made by another prominent American atheist, Dan Dennett [What Should Replace Religion?].

I don't get it. Why should atheists have to form their own "churches"? In Canada these services are provided by local community centres—there are four within a short drive of were I live. The one within walking distance is called South Common Community Centre. It has a swimming pool (see photo above), a public library, many gyms and exercise rooms, and meeting rooms. There's daycare and classes of various sorts, dozens of volunteer organizations and support groups, swimming lessons for adults and children and lots more. The community centres are funded by civic government and paid for by taxes. They are open to everybody.

Some of them rent out space for church services on Sundays but they are definitely secular. They are not atheist centres.

The best way to provide the services that people need has already been invented. It's called socialism. It's wrong to assume that the only solution is competing services supplied by various religious churches plus one non-religious church.

Is it impossible to work in America toward the goal of secular social services for all? Is that why the only solution seems to be for atheists/humanists to form their own competing religion to provide those services for nonbelievers?

Friday, August 17, 2012

What Would Disprove Jerry Coyne's Version of Evolution?

Jerry Coyne has a particular view of evolution—one that conflates fact, theory, and history [What would disprove evolution?].

Based on his version of evolution, he then offers some examples of what it would take to disprove evolution.

I was tempted last month to challenge his views but I kept putting it off. Now, Ryan Gregory has done the job, and it's an admirable job.

I agree with everything Gregory says at: An example of why it is important to distinguish evolution as fact, theory, and path.

Please leave comments on Ryan's site.

Based on his version of evolution, he then offers some examples of what it would take to disprove evolution.

I was tempted last month to challenge his views but I kept putting it off. Now, Ryan Gregory has done the job, and it's an admirable job.

I agree with everything Gregory says at: An example of why it is important to distinguish evolution as fact, theory, and path.

Please leave comments on Ryan's site.

Disproving Evolution

Elsewhere on the internet there's a discussion about whether evolution can be disproved by simply finding a fossil out of order.

Here's what I said on Facebook ...

Here's what I said on Facebook ...

The statement is untrue. If we discover that a given species is older than we thought then we will just revise our view of the history of life on Earth. It will not disprove the fact of evolution and it will have no effect on evolutionary theory. It is a mistake to link the truth of evolution to our current understanding of the history of life. That history can be easily changed without threatening evolution.

Thursday, August 16, 2012

R. Elsiabeth Cornwell Talks About Social Networks

R. Elisabeth Cornwell is Executive Director of the Richard Dawkins Foundation (US). She has a Ph.D. in psychology and her day job is Professor at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs.

Here's Cornwell giving a talk at TAM2012. It makes me cringe but is it just me? Apparently not if you read the comments at YouTube.

She talks a lot about bullies and their presumed psychiatric problems but she doesn't give any examples. Who is she thinking about? Jonathan Wells? PZ Myers? Margaret Thatcher? Rush Limaugh? Stephen Jay Gould? Jerry Falwell? Ken Miller? Ann Coulter? Christopher Hitchens? Thomas Huxley? Rachel Maddow? Richard Dawkins?

It would have been nice to see the difference between pre-internet "bullies" and those on the internet. Are there any example of people who were "civilized" before they got on the internet but became bullies once they started a blog?

Here's Cornwell giving a talk at TAM2012. It makes me cringe but is it just me? Apparently not if you read the comments at YouTube.

She talks a lot about bullies and their presumed psychiatric problems but she doesn't give any examples. Who is she thinking about? Jonathan Wells? PZ Myers? Margaret Thatcher? Rush Limaugh? Stephen Jay Gould? Jerry Falwell? Ken Miller? Ann Coulter? Christopher Hitchens? Thomas Huxley? Rachel Maddow? Richard Dawkins?

It would have been nice to see the difference between pre-internet "bullies" and those on the internet. Are there any example of people who were "civilized" before they got on the internet but became bullies once they started a blog?

Stipends for Graduate Students

Here's what we pay our slaves graduate students while they are working toward their degrees. How does it compare with other biochemistry departments?

Biochemistry Graduate Student Stipends for 2012-2013

M.Sc. students

Domestic Students

$17,000 living allowance plus tuition ($7,160.00) and incidental fees ($1,241.52) = $25,401.52

International Students

$17,000 living allowance plus tuition ($16,886.00) and incidental fees ($1,241.52) AND UHIP ($684.00) = $35,811.52

Ph.D. students

Domestic Students

$19,000 living allowance plus tuition ($7,160.00) and incidental fees ($1,241.52) = $27,401.52

International Students

$19,000 living allowance plus tuition ($16,886.00) and incidental fees ($1,241.52) AND UHIP ($684.00) = $37,811.52

(UHIP is the University Health Insurance Plan)

My graduate student stipend in 1968 was $3000, which is $19,500 in 2012 dollars. I don't remember how much tuition and the health plan cost. We lived in subsidized housing, The rent was $56 per month.

We have about 140 graduate students in our department. Many of them are in the photo along with several much older "students" who earn a lot more money.

Biochemistry Graduate Student Stipends for 2012-2013

M.Sc. students

Domestic Students

$17,000 living allowance plus tuition ($7,160.00) and incidental fees ($1,241.52) = $25,401.52

International Students

$17,000 living allowance plus tuition ($16,886.00) and incidental fees ($1,241.52) AND UHIP ($684.00) = $35,811.52

Ph.D. students

Domestic Students

$19,000 living allowance plus tuition ($7,160.00) and incidental fees ($1,241.52) = $27,401.52

International Students

$19,000 living allowance plus tuition ($16,886.00) and incidental fees ($1,241.52) AND UHIP ($684.00) = $37,811.52

(UHIP is the University Health Insurance Plan)

My graduate student stipend in 1968 was $3000, which is $19,500 in 2012 dollars. I don't remember how much tuition and the health plan cost. We lived in subsidized housing, The rent was $56 per month.

We have about 140 graduate students in our department. Many of them are in the photo along with several much older "students" who earn a lot more money.

Wednesday, August 15, 2012

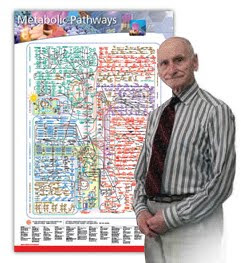

Donald E. Nicholson (1916 - 2012)

Donald Nicholson died last May. He was 96 years old.

Nicholson was a professor of biochemistry at the University of Leeds in the United Kingdom. He started drawing metabolic charts back in 1955 and they gradually evolved into the works of art that you have seen in all the textbooks and on the walls of labs in offices in biochemistry departments around the world. I doubt that there's a single biochemist that hasn't studied these charts at some time during their undergraduate experience.

Lately his metabolic charts have been the property of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (IUBMB) but many of them have been marketed by Sigma-Aldrich [Metabolic Pathways].

Recent additions have included several minimaps of specific pathways such as those involved in lipid metabolism, glycolysis, the urea cycle etc. It's sad that we won't see any additions to this collection or any updates.

Nicholson was a professor of biochemistry at the University of Leeds in the United Kingdom. He started drawing metabolic charts back in 1955 and they gradually evolved into the works of art that you have seen in all the textbooks and on the walls of labs in offices in biochemistry departments around the world. I doubt that there's a single biochemist that hasn't studied these charts at some time during their undergraduate experience.

Lately his metabolic charts have been the property of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (IUBMB) but many of them have been marketed by Sigma-Aldrich [Metabolic Pathways].

Recent additions have included several minimaps of specific pathways such as those involved in lipid metabolism, glycolysis, the urea cycle etc. It's sad that we won't see any additions to this collection or any updates.

A Sophisticated Theologian Explains Why You Should Believe in God

Modern atheists are often accused of being ignorant of the most up-to-date arguments for the existence of god(s).1 We are told that there's a very sophisticated group of theologians out there who shouldn't be ignored.

Whenever we ask for those "sophisticated" arguments for the existence of god(s) we are directed to various Courtier's Replies discussing how to rationalize the properties of various gods. They all begin with the assumption that god(s) exist. As I pointed out earlier, there's no reason why an atheist should care about things like the problem of evil. It makes about as much sense as debating the cut of the Emperor's new clothes or the stylishness of his new hat.

Alvin Plantinga is one of these "sophisticated" theologians. Listen to him explain why atheists should believe in god(s). Is this really the best they can do?

Whenever we ask for those "sophisticated" arguments for the existence of god(s) we are directed to various Courtier's Replies discussing how to rationalize the properties of various gods. They all begin with the assumption that god(s) exist. As I pointed out earlier, there's no reason why an atheist should care about things like the problem of evil. It makes about as much sense as debating the cut of the Emperor's new clothes or the stylishness of his new hat.

Alvin Plantinga is one of these "sophisticated" theologians. Listen to him explain why atheists should believe in god(s). Is this really the best they can do?

1. The second most common complaint is that we don't even have good arguments for atheism—at least not as good as those thinkers of the 20th century who were full of angst over not having a god to believe in. Apparently modern atheists aren't very sophisticated unless they are contemplating suicide.

[Hat Tip: Jerry Coyne: Plantinga on why he believes in God, dislikes the New Atheists, and finds naturalism and evolution incompatible.]

Monday, August 13, 2012

Monday's Molecule #181

Last week's molecule was an intermediate in some amino acid biosynthesis pathways and the enzyme that makes it is the target of Roundup®. Replacing this enzyme with a Roundup® resistant version yields genetically modified food plants [Monday's Molecule #180].

This week's molecule is a lot more complicated. You need to identify the specific type of molecule. Defective metabolism of this molecule is associated with a famous disease. Name the disease.

Post your answers as a comment. I'll hold off releasing any comments for 24 hours. The first one with the correct answer wins. I will only post mostly correct answers to avoid embarrassment. The winner will be treated to a free lunch.

There could be two winners. If the first correct answer isn't from an undergraduate student then I'll select a second winner from those undergraduates who post the correct answer. You will need to identify yourself as an undergraduate in order to win. (Put "undergraduate" at the bottom of your comment.)

Some past winners are from distant lands so their chances of taking up my offer of a free lunch are slim. (That's why I can afford to do this!)

In order to win you must post your correct name. Anonymous and pseudoanonymous commenters can't win the free lunch.

Winners will have to contact me by email to arrange a lunch date. Please try and beat the regular winners. Most of them live far away and I'll never get to take them to lunch. This makes me sad.

Comments are invisible for 24 hours. Comments are now open.

UPDATE: The molecule is ganglioside GM2. Defects in ganglioside synthesis are responsible for a number of genetic diseases in humans including Tay-Sachs disease. This is the same molecule featured in Monday's Molecule #162 back on March 19, 2012. There was no winner that time.

This week's winner is Matt McFarlane, an undergraduate. He lives in Canada but he's quite far away and probably won't make it for lunch.

Winners

Nov. 2009: Jason Oakley, Alex Ling

Oct. 17: Bill Chaney, Roger Fan

Oct. 24: DK

Oct. 31: Joseph C. Somody

Nov. 7: Jason Oakley

Nov. 15: Thomas Ferraro, Vipulan Vigneswaran

Nov. 21: Vipulan Vigneswaran (honorary mention to Raul A. Félix de Sousa)

Nov. 28: Philip Rodger

Dec. 5: 凌嘉誠 (Alex Ling)

Dec. 12: Bill Chaney

Dec. 19: Joseph C. Somody

Jan. 9: Dima Klenchin

Jan. 23: David Schuller

Jan. 30: Peter Monaghan

Feb. 7: Thomas Ferraro, Charles Motraghi

Feb. 13: Joseph C. Somody

March 5: Albi Celaj

March 12: Bill Chaney, Raul A. Félix de Sousa

March 19: no winner

March 26: John Runnels, Raul A. Félix de Sousa

April 2: Sean Ridout

April 9: no winner

April 16: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

April 23: Dima Klenchin, Deena Allan

April 30: Sean Ridout

May 7: Matt McFarlane

May 14: no winner

May 21: no winner

May 29: Mike Hamilton, Dmitri Tchigvintsev

June 4: Bill Chaney, Matt McFarlane

June 18: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

June 25: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 2: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 16: Sean Ridout, William Grecia

July 23: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 30: Bill Chaney and Raul A. Félix de Sousa

Aug. 7: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

Aug. 13: Matt McFarlane

This week's molecule is a lot more complicated. You need to identify the specific type of molecule. Defective metabolism of this molecule is associated with a famous disease. Name the disease.

Post your answers as a comment. I'll hold off releasing any comments for 24 hours. The first one with the correct answer wins. I will only post mostly correct answers to avoid embarrassment. The winner will be treated to a free lunch.

There could be two winners. If the first correct answer isn't from an undergraduate student then I'll select a second winner from those undergraduates who post the correct answer. You will need to identify yourself as an undergraduate in order to win. (Put "undergraduate" at the bottom of your comment.)

Some past winners are from distant lands so their chances of taking up my offer of a free lunch are slim. (That's why I can afford to do this!)

In order to win you must post your correct name. Anonymous and pseudoanonymous commenters can't win the free lunch.

Winners will have to contact me by email to arrange a lunch date. Please try and beat the regular winners. Most of them live far away and I'll never get to take them to lunch. This makes me sad.

UPDATE: The molecule is ganglioside GM2. Defects in ganglioside synthesis are responsible for a number of genetic diseases in humans including Tay-Sachs disease. This is the same molecule featured in Monday's Molecule #162 back on March 19, 2012. There was no winner that time.

This week's winner is Matt McFarlane, an undergraduate. He lives in Canada but he's quite far away and probably won't make it for lunch.

Winners

Nov. 2009: Jason Oakley, Alex Ling

Oct. 17: Bill Chaney, Roger Fan

Oct. 24: DK

Oct. 31: Joseph C. Somody

Nov. 7: Jason Oakley

Nov. 15: Thomas Ferraro, Vipulan Vigneswaran

Nov. 21: Vipulan Vigneswaran (honorary mention to Raul A. Félix de Sousa)

Nov. 28: Philip Rodger

Dec. 5: 凌嘉誠 (Alex Ling)

Dec. 12: Bill Chaney

Dec. 19: Joseph C. Somody

Jan. 9: Dima Klenchin

Jan. 23: David Schuller

Jan. 30: Peter Monaghan

Feb. 7: Thomas Ferraro, Charles Motraghi

Feb. 13: Joseph C. Somody

March 5: Albi Celaj

March 12: Bill Chaney, Raul A. Félix de Sousa

March 19: no winner

March 26: John Runnels, Raul A. Félix de Sousa

April 2: Sean Ridout

April 9: no winner

April 16: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

April 23: Dima Klenchin, Deena Allan

April 30: Sean Ridout

May 7: Matt McFarlane

May 14: no winner

May 21: no winner

May 29: Mike Hamilton, Dmitri Tchigvintsev

June 4: Bill Chaney, Matt McFarlane

June 18: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

June 25: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 2: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 16: Sean Ridout, William Grecia

July 23: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 30: Bill Chaney and Raul A. Félix de Sousa

Aug. 7: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

Aug. 13: Matt McFarlane

An Example of "Directed" Mutation and an Idiotic "Gotcha"

There's nothing in modern evolutionary theory that allows for mutations that arise specifically because they will produce a future benefit. That's why we say that mutations are "random" with respect to outcome.

There's nothing in the known history of life that suggests it has a purpose or direction. In particular, there's nothing to suggest that 3.5 billion years of evolution were just advanced preparation for the appearance of Home sapiens. That's why we say that evolution appears unguided and purposeless [Is "Unguided" Part of Modern Evolutionary Theory?]. And that's why anyone who says that life shows evidence of purpose is not being scientific.

Creationists aren't happy about this so they will go to extraordinary lengths to wiggle out of the inescapable conclusion based on solid evidence. The usual excuse is to postulate that god is very sneaky. He/she/it makes a huge effort to hide his/her/its manipulations so that it only appears that evolution is unguided and purposeless. The clever creationists aren't fooled by this sneaky god; they can detect its deception, but scientists can't.

Read more »

There's nothing in the known history of life that suggests it has a purpose or direction. In particular, there's nothing to suggest that 3.5 billion years of evolution were just advanced preparation for the appearance of Home sapiens. That's why we say that evolution appears unguided and purposeless [Is "Unguided" Part of Modern Evolutionary Theory?]. And that's why anyone who says that life shows evidence of purpose is not being scientific.

Creationists aren't happy about this so they will go to extraordinary lengths to wiggle out of the inescapable conclusion based on solid evidence. The usual excuse is to postulate that god is very sneaky. He/she/it makes a huge effort to hide his/her/its manipulations so that it only appears that evolution is unguided and purposeless. The clever creationists aren't fooled by this sneaky god; they can detect its deception, but scientists can't.

Read more »

Sunday, August 12, 2012

C.H. Cosgrove, An Ancient Christian Hymn with Musical Notation

CHARLES H. COSGROVE

An Ancient Christian Hymn with Musical Notation

Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 1786: Text and Commentary

In this book, Charles Cosgrove undertakes a comprehensive examination of Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 1786, an ancient Greek Christian hymn dating to the late third century that offers the most ancient surviving example of a notated Christian melody. The author analyzes the text and music of the hymn, situating it in the context of the Greek literary and hymnic tradition, ancient Greek music, early Christian liturgy and devotion, and the social setting of Oxyrhynchus circa 300 C.E. The broad sweep of the commentary touches the interests of classical philologists, specialists in ancient Greek music, church historians, and students of church music history.

Text and Commentary

2011. XI, 232 pages. STAC 65

ISBN 978-3-16-150923-0

sewn paper € 69.00

An Ancient Christian Hymn with Musical Notation

Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 1786: Text and Commentary

In this book, Charles Cosgrove undertakes a comprehensive examination of Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 1786, an ancient Greek Christian hymn dating to the late third century that offers the most ancient surviving example of a notated Christian melody. The author analyzes the text and music of the hymn, situating it in the context of the Greek literary and hymnic tradition, ancient Greek music, early Christian liturgy and devotion, and the social setting of Oxyrhynchus circa 300 C.E. The broad sweep of the commentary touches the interests of classical philologists, specialists in ancient Greek music, church historians, and students of church music history.

Text and Commentary

2011. XI, 232 pages. STAC 65

ISBN 978-3-16-150923-0

sewn paper € 69.00

J.H.F. Dijkstra, Syene I: The Figural and Textual Graffiti from the Temple of Isis at Aswan

In Ancient Egypt, especially in the Graeco-Roman period, the practice was widespread for worshippers to leave graffiti on the walls of temples, often with religious intentions. Graffiti from temples are therefore a treasure trove for the study of personal piety in Ancient Egypt, as well as in later periods when temples remained attractive to Christians. The present study, the first final report of the excavations at ancient Syene (Aswan) conducted since the year 2000 by the Swiss Institute for Architectural and Archaeological Research on Ancient Egypt and the Supreme Council of Antiquities, is among the first to study together all graffiti (352 in total, both figures and texts) from a single temple, the temple of Isis at Aswan, ranging in date from the 3rd century BCE until the 19th century CE, and to place them within their architectural context. The graffiti provide us with many fascinating snapshots of religious life, and other activities, in the long period in which the building was used and reused.

25.06.2012;

239 Seiten, mit 36 s/w Tafeln und einer CD; 26,5 x 35cm; Gebunden; Englisch;

ISBN 978-3-8053-4395-4

Jitse Dijkstra is Associate Professor of Classics at the University of Ottawa. He has published widely on several aspects of Graeco-Roman and Late Antique Egypt, in particular the monograph Philae and the End of Ancient Egyptian Religion. A Regional Study of Religious Transformation (298-642 CE) (2008). Since 2001, he is a member of the joint archaeological mission of the Swiss Institute and the Supreme Council of Antiquities at Aswan.

25.06.2012;

239 Seiten, mit 36 s/w Tafeln und einer CD; 26,5 x 35cm; Gebunden; Englisch;

ISBN 978-3-8053-4395-4

Jitse Dijkstra is Associate Professor of Classics at the University of Ottawa. He has published widely on several aspects of Graeco-Roman and Late Antique Egypt, in particular the monograph Philae and the End of Ancient Egyptian Religion. A Regional Study of Religious Transformation (298-642 CE) (2008). Since 2001, he is a member of the joint archaeological mission of the Swiss Institute and the Supreme Council of Antiquities at Aswan.

Saturday, August 11, 2012

Humanities Aren't Science? More's the Pity

Science is a way of knowing that is evidence based and requires rational thinking and healthy skepticism. It's the only successful way of knowing that has ever been invented.

Whenever investigators in the humanities discover new knowledge it turns out that they have been using a scientific approach. They've been thinking like a scientist. What else could they be doing?

Maria Konnikova is a graduate student in psychology at Columbia University. She writes in Scientific American that Humanities aren’t a science. Stop treating them like one.

Well, it's certainly true that many disciplines in the humanities are very unscientific—evolutionary psychology comes to mind—but this is one of the first times I've ever heard someone be proud of the fact that they don't think scientifically. Why in the world would she say that?

Turns out she's confused about what science is and what it isn't. She thinks that science requires lots of quantitative data and lots of mathematics and statistics.

Maybe Konnikova is just saying that humanities disciplines are not chemistry, physics, biology or geology? Nah, that's too obvious. It doesn't merit an article in "Scientific" American. Maybe we'll find out what she really means when her book comes out in January. It's title is: Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes. Did Sherlock Holmes think like a scientist or did he think like someone in the humanities?

Whenever investigators in the humanities discover new knowledge it turns out that they have been using a scientific approach. They've been thinking like a scientist. What else could they be doing?

Maria Konnikova is a graduate student in psychology at Columbia University. She writes in Scientific American that Humanities aren’t a science. Stop treating them like one.

Well, it's certainly true that many disciplines in the humanities are very unscientific—evolutionary psychology comes to mind—but this is one of the first times I've ever heard someone be proud of the fact that they don't think scientifically. Why in the world would she say that?

Turns out she's confused about what science is and what it isn't. She thinks that science requires lots of quantitative data and lots of mathematics and statistics.

Sometimes, there is no easy approach to studying the intricate vagaries that are the human mind and human behavior. Sometimes, we have to be okay with qualitative questions and approaches that, while reliable and valid and experimentally sound, do not lend themselves to an easy linear narrative—or a narrative that has a base in hard science or concrete math and statistics. Psychology is not a natural science. It’s a social science. And it shouldn’t try to be what it’s not.Hmmmm ... that might explain a lot. I guess if you are seeking knowledge in the social sciences it's okay to use a non-scientific approach to gain knowledge. I wonder what approach they follow? Do they pray for guidance? Use a Ouija board? Or do they just make stuff up?

Maybe Konnikova is just saying that humanities disciplines are not chemistry, physics, biology or geology? Nah, that's too obvious. It doesn't merit an article in "Scientific" American. Maybe we'll find out what she really means when her book comes out in January. It's title is: Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes. Did Sherlock Holmes think like a scientist or did he think like someone in the humanities?

[Hat Tip: Mike the Mad Biologist]

Science and Christianity—Different Ways of Finding Truth?

Chris Mulherin is an Anglican Minister who studies the relationship of science and religion. In this video he claims that science and religion are compatible. Specifically, science and Christianity are compatible.

UPDATE: Eric MacDonald does an excellent job of taking down Chris Mulherin in Science and Religion Again!. MacDonald is a former Anglican priest. (Hat Tip: Jerry Coyne.

He doesn't explain how rising from the dead, miracles, souls, heaven, and a Bible full of lies are compatible with science. Instead, he concentrates on the old saw of different magisteria. Christianity answers different questions than science and discovers different truths.