The situation is perfectly clear. Everyone cares about good science education and Ed can go climb a tree for suggesting otherwise. But some of us also believe that it does no good to pander and condescend to people's religious beliefs by telling them that there is no conflict between science and religion. There is a conflict, it is a big one, and most people find that obvious. Clever people like Miller and Collins can find imaginative ways of reconciling the two, but few people are buying it.Yep. There's a conflict between science and religion, and ignoring it ain't gonna make it go away.

Thursday, November 30, 2006

Jason Rosenhouse on Science v Religion

Jason Rosenhouse has a lengthy posting over on EvolutionBlog. It's well worth reading. Here's a snippet ...

Psiphon Web censorship bypass tool

The University of Toronto announces the release of Psiphon, a software tool that bypasses internet censorship.

Psiphon is a downloadable program (available at http://psiphon.civisec.org/) that essentially lets someone turn a home computer into a server. Once psiphon is installed, the operator of the host computer sends a unique web address to friends or family members living in one of the 40 countries worldwide where Internet use is censored. Those in the censored country can then connect to the “server” and use it as a “host computer” to surf the Net and gain access to websites censored or blocked in their own country.This means they'll be able to read Sandwalk and Pharyngula!

“Their connection is encrypted, so no one can eavesdrop on it,” [Professor Ronald] Deibert said. “It’s an encrypted communication link between two computers. So authorities wouldn’t be able to spot what websites are being visited by the user at risk.”

National Science Teachers Association

The original kurfluffle over the donation of "An Inconvenient Truth" DVDs to the National Teachers Association was prompted by an article in The Washington Post by Laurie David, one of the show's producers. Several bloggers were highly critical of NSTA, based on the "facts" in the newspaper article.

NSTA has now posted a press release on the NSTA Website.

There appears to be more to this story than we originally thought. Several bloggers have commented [BadAstronomy, No Se Nada, A Blog Around the Clock, Discovering Biology in a Digital World].

NSTA has now posted a press release on the NSTA Website.

Over the past few days, NSTA and film producer Laurie David have been discussing her offer to provide NSTA with copies of the DVD "An Inconvenient Truth" to mass distribute to our members. On November 29, 2006, NSTA's Board of Directors held a telephone conference to review Ms. David's request. In an effort to accommodate her request without violating the Board's 2001 policy prohibiting product endorsement, and to provide science educators with the opportunity to take advantage of the educational opportunities presented by films such as this, NSTA has offered to greatly expand the scope of the potential target audience identified in her initial request.

NSTA established its non-endorsement policy to formalize our position that the association would not send third-party materials to our members without their consent or request. NSTA looks forward to working with Ms. David to ensure that there are many options for publicizing the availability of the DVD to the national science education community, and to broaden the conversation on the important topic of global warming.

There appears to be more to this story than we originally thought. Several bloggers have commented [BadAstronomy, No Se Nada, A Blog Around the Clock, Discovering Biology in a Digital World].

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

The Three Domain Hypothesis (part 4)

Ludwig and Schleifer question the reliability of the SSU tree. They begin by comparing trees constructed from the small ribosomal RNA subunit (SSU) and the large ribosomal RNA subunit (LSU). The example they use is 18 species of Enterococcus and they show that there are significant differences between the two trees. Surprisingly, they dismiss these differences as “minor local differences.” These authors are convinced that “SSU and LSU rRNA genes fulfill the requirements of ideal phylogenetic markers to an extent far greater than do protein coding genes.”

In spite of this bias, they compiled a database of protein trees from conserved genes that are found in all three of the proposed Domains. According to them, the Three Domain Hypothesis is supported by EF-Tu, the large subunits of RNA polymerase, Hsp60, and some aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aspartyl, leucyl, tryptophanyl, and tyrosyl).

The Three Domain Hypothesis is refuted by ATPase, DNA gyrase A, DNA gyrase B, Hsp70, RecA, and some aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Note the inclusion of ATPase in this list. The phylogeny of ATPase was one of the strongest bits of evidence for the Three Domain Hypothesis back in 1989 but further work has shown that these genes (proteins) now refute the hypothesis.

My own favorite is the HSP70 gene family, arguably the most highly conserved gene in all of biology and therefore an excellent candidate for studies of deep phylogeny. Hsp70 is the main chaperone in all species. It is responsible for the correct folding of proteins as they are synthesized. It forms a complex with DnaJ and GrpE in bacteria and similar proteins in eukaryotes. The complex associates with the translation machinery (ribomes etc.) during protein synthesis.

The conflict between trees constructed with HSP70 and the ribosomal RNA trees has been known for a long time. The actual pattern of the HSP70 tree can be interpreted in two different ways depending on where you place the root [see 1995] but neither one agrees with the Three Domain Hypothesis.

Here’s an example of an HSP70 tree that I just created using the latest sequences. It’s fairly typical of the trees that do not support the Three Domain Hypothesis. Eukaryotes cluster as a monophyletic group (lower left) and all prokaryotes form another distinct clade. The archaebacteria sequences (black dots) do not form a single clade, let alone a “domain.” Instead, they tend to be dispersed among the other bacterial groups.

Note that this tree, like many others, shows numerous short branches at the bottom of the bacteria tree suggesting that the diversity among bacteria is ancient. Phillippe and Forterre (1999) were among the first to document the serious differences between conserved protein trees and rRNA trees in “The Rooting of the Universal Tree of Life Is Not Reliable” (J. Mol. Evol. 49:509-523). It’s worth quoting their abstract in order to emphasize the controversy since Ludwig and Schleifer don’t do a very good job.

Several composite universal trees connected by an ancestral gene duplication have been used to root the universal tree of life. In all cases, this root turned out to be in the eubacterial branch. However, the validity of results obtained from comparative sequence analysis has recently been questioned, in particular, in the case of ancient phylogenies. For example, it has been shown that several eukaryotic groups are misplaced in ribosomal RNA or elongation factor trees because of unequal rates of evolution and mutational saturation. Furthermore, the addition of new sequences to data sets has often turned apparently reasonable phylogenies into confused ones. We have thus revisited all composite protein trees that have been used to root the universal tree of life up to now (elongation factors, ATPases, tRNA synthetases, carbamoyl phosphate synthetases, signal recognition particle proteins) with updated data sets. In general, the two prokaryotic domains were not monophyletic with several aberrant groupings at different levels of the tree. Furthermore, the respective phylogenies contradicted each others, so that various ad hoc scenarios (paralogy or lateral gene transfer) must be proposed in order to obtain the traditional Archaebacteria-Eukaryota sisterhood. More importantly, all of the markers are heavily saturated with respect to amino acid substitutions. As phylogenies inferred from saturated data sets are extremely sensitive to differences in evolutionary rates, present phylogenies used to root the universal tree of life could be biased by the phenomenon of long branch attraction. Since the eubacterial branch was always the longest one, the eubacterial rooting could be explained by an attraction between this branch and the long branch of the outgroup. Finally, we suggested that an eukaryotic rooting could be a more fruitful working hypothesis, as it provides, for example, a simple explanation to the high genetic similarity of Archaebacteria and Eubacteria inferred from complete genome analysis.The problem is obvious. All trees, RNA and protein, have potential problems of saturation and long branch attraction. Although Ludwig and Schleifer argue in favor of the ribosomal RNA tree, there is still serious debate over which sequences are revealing the “true” phylogeny. Are there good reasons for rejecting those trees that refute the Three Domain Hypothesis as it's supporters maintain?

Microbobial Phylogeny and Evolution: Concepts and Controversies Jan Sapp, ed., Oxford University Press, Oxford UK (2005)

Jan Sapp The Bacterium’s Place in Nature

Norman Pace The Large-Scale Structure of the Tree of Life.

Woflgang Ludwig and Karl-Heinz Schleifer The Molecular Phylogeny of Bacteria Based on Conserved Genes.

Carl Woese Evolving Biological Organization.

W. Ford Doolittle If the Tree of Life Fell, Would it Make a Sound?.

William Martin Woe Is the Tree of Life.

Radhey Gupta Molecular Sequences and the Early History of Life.

C. G. Kurland Paradigm Lost.

Iraq: The Hidden Story

This show was broadcast on television in the UK. The Brits are better informed than we are.

Nobel Laureates: Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1964.

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1964."for her determinations by X-ray techniques of the structures of important biochemical substances"

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin (1910-1994) was one of the pioneers of X-ray crystallography. Her many achievements include the first X-ray diffraction pattern of a protein in 1934 (with J.D. Bernal), and the structures of penicillin, vitamin B12, insulin, and tobacco mosaic virus. She did most of her work in Oxford from 1934 until her retirement in 1979.

Her Nobel Prize was in recognition of her enormous contributions to the field of X-ray crystallography, especially her work on the structure of vitamin B12. When she published the structure in 1954, it was the largest molecule whose three dimensional structure had been solved.

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Neil deGrasse Tyson and Richard Dawkins

This is the video clip that so many of my colleagues are excited about. They think Neil deGrasse Tyson has hit the nail on the head. They agree with him that Dawkins is being "insensitive" when he criticizes religion.

I'm not familiar with Neil deGrasse Tyson. Is he famous in America? Is he a good educator? Is he effective? Has he been going around the country giving lectures where he gently and kindly urges his audiences to question their religious beliefs? Has he been softly pleading with Americans to respect atheists? Has he been speaking out, quietly, against the Ted Haggards and Jerry Falwells of this world? Is his strategy working?

Richard Dawkins has done more in the past two months to stimulate a dialogue on religion than all the rest of us have done in five decades. The blogs are full of excitement about atheism and religion. Dawkins has been at dozens of universities, appeared on dozens of TV shows, and been featured in major articles in most newspapers. The debate made the cover of Time magazine. There have been several symposia like the one Tyson was invited to. There wouldn't even have been a symposium without Dawkins.

People all over North America are questioning religion. I've seen it on the streets in my own neighborhood and overheard discussions in the restaurants. All of a sudden, people are realizing there are atheists in their midst—and they're not so bad after all. Ask yourself this: how does the Dawkins' form of education compare with the efforts of people like Neil deGrasse Tysons?

I'm not familiar with Neil deGrasse Tyson. Is he famous in America? Is he a good educator? Is he effective? Has he been going around the country giving lectures where he gently and kindly urges his audiences to question their religious beliefs? Has he been softly pleading with Americans to respect atheists? Has he been speaking out, quietly, against the Ted Haggards and Jerry Falwells of this world? Is his strategy working?

Richard Dawkins has done more in the past two months to stimulate a dialogue on religion than all the rest of us have done in five decades. The blogs are full of excitement about atheism and religion. Dawkins has been at dozens of universities, appeared on dozens of TV shows, and been featured in major articles in most newspapers. The debate made the cover of Time magazine. There have been several symposia like the one Tyson was invited to. There wouldn't even have been a symposium without Dawkins.

People all over North America are questioning religion. I've seen it on the streets in my own neighborhood and overheard discussions in the restaurants. All of a sudden, people are realizing there are atheists in their midst—and they're not so bad after all. Ask yourself this: how does the Dawkins' form of education compare with the efforts of people like Neil deGrasse Tysons?

The Legend of Zelda

Check out the Nintendo site for cool videos documenting the history of The Legend of Zelda. Part 1 is included below.

I remember when we got out first game box back in 1988. We got it for the kids, it was very educational.

Of course we had to try one of the games just to see what all the excitement was about. My kids were only ten or eleven years old so I had to show them all the tricks of navigating the maze in Zelda. If I remember correctly, it was me who taught them everything they know about computer gaming. Well, almost everything ... Okay, so they whipped my butt. They got lucky.

I remember when we got out first game box back in 1988. We got it for the kids, it was very educational.

Of course we had to try one of the games just to see what all the excitement was about. My kids were only ten or eleven years old so I had to show them all the tricks of navigating the maze in Zelda. If I remember correctly, it was me who taught them everything they know about computer gaming. Well, almost everything ... Okay, so they whipped my butt. They got lucky.

Linux Commands

Here's a list of the top 200 Linux commands. Some of them are very useful, especially for us old fogies. For example, I use "whoami" at least once a day.

Here's a list of the top 200 Linux commands. Some of them are very useful, especially for us old fogies. For example, I use "whoami" at least once a day.

Some of them will drive you crazy. Don't even think about typing "vi" unless you're prepared to throw the keyboard into the monitor. "Format" is lots of fun, try it with every letter of the alphabet.

"Grep" isn't what you think it is.

The computer is "Darwin." It's owned by David Greig (DIG) and lives in my office. "Darwin" is the server for the newsgroups talk.origins and sci.bio.evolution. DIG moderates talk.origins with a lot of help from Darwin. Josh Hayes attempts to control sci.bio.evolution—it's a losing battle.

I think I'll try out some of the more unusual Linux commands on Darwin. I wonder what "kill" does? ....

Monday, November 27, 2006

Something to be Proud of?

Gene Expression has a new icon in the sidebar. Apparently the author is proud to be an appeaser.

Gene Expression has a new icon in the sidebar. Apparently the author is proud to be an appeaser.For the record, here's what it means to be a Neville Chamberlain Atheist. It means you're happy to attack Intelligent Design Creationists like Micheal Denton (Nature's Destiny) and Michael Behe (Darwin's Black Box) for mixing science and religion. But, you don't say a word when Ken Miller (Finding Darwin's God), Francis Collins (The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief) and the Rev. Ted Peters (Evolution from Creation to New Creation) spout equally bad religious nonsense in the name of science.

The Neville Chamberlain Atheists object when Behe talks about intelligent design but mum's the word when Ken Miller talks about how God tweaks mutations to get what He wants. Hypocrisy is a strange thing to be proud of.

He must be joking, right?

An Inconvenient Truth

If you haven't seen it, get yourself to a video store tomorrow. Then read the debate about whether the National Science Teachers Association should accept 50,000 free DVD's [What's up NSTA?].

I don't agree with PZ on this one. The science is good but Al Gore is exploring the possibility of a run for the Democratic nomination in 2008. I saw him in action for three days at Chautauqua last summer. If it were Carl Sagan I'd say NSTA should show the DVDs in every classroom but it's silly to pretend that Al Gore isn't a politician.

I don't agree with PZ on this one. The science is good but Al Gore is exploring the possibility of a run for the Democratic nomination in 2008. I saw him in action for three days at Chautauqua last summer. If it were Carl Sagan I'd say NSTA should show the DVDs in every classroom but it's silly to pretend that Al Gore isn't a politician.

Who Let Him Out on his Own?

Depak Chopra demonstrates, once again, why we call them IDiots. PZ Myers has pointed out the foolishness in his posting on Pharyngula, "Oh, no...not more Chopra!". The thrust of the rant has something to do with seeing things in your mind. (I didn't pay much attention, it's kindergarten stuff.) Apparently, the fact that you can create an image of a yellow flower means that God exists. PZ tells it like it is but he stops short of the important part of Chorpa's article where Chopra says,

Why does the Huffington Post put up with this IDiot?

Yet you assume--as do all who fall for the superstition of materialism--that flowers and the color yellow exist 'out there' in the world and are photographically reproduced by the brain, acting as a camera made of organic tissue. In fact, existence of flowers shifts mysteriously once it is closely examined. The experience of sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell is created in consciousness. Molecules don't assemble in your head to make the sound of a trumpet blaring in a brass band, for example. The brain is silent. So where does the world of sights and sounds come from?I can't resist. Yes, Depak, turning the vibrating air molecules that come out of your mouth into meaningful words has never been seen or measured. And your point is?

Materialists cannot offer any reasonable explanation. The fact is that an enormous gap exists between any physical, measurable event and our perception. If I talk to you, all I am doing is vibrating air with my vocal cords. Every aspect of that event can be seen and measured, but turning those vibrating air molecules into meaningful words has never been seen or measured. It can't be.

Why does the Huffington Post put up with this IDiot?

Recording Lectures

Every time I give a lecture there’s a bunch of recorders in front of me. Following the lecture, there’s an active trade in lecture recordings on our student newsgroups.

I have mixed feeling about this. On the one hand, I understand why students would want to take advantage of cheap technology to make a permanent record of my words of wisdom. :-)

On the other hand, my words aren’t always wise and I don’t want students to memorize everything I say without checking it against the textbook and other sources. Lecture recordings should be supplements to learning and not the only source. (Don’t get me started about podcasts!)

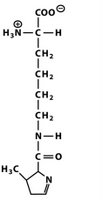

This point was brought home in one of the threads on our student forums. The students in one of our biochemistry courses had just finished a midterm exam. One of the multiple choice questions was about cholesterol. For those of you who haven’t committed the structure of cholesterol to memory—I am one—I’m including a picture. The description in the textbook (it happens to be my textbook) is ....

I then go on to describe cholesterol, an important steroid.

I then go on to describe cholesterol, an important steroid.

Choice “C” in the multiple choice question referred to the 4-ring structure of cholesterol. It was a correct choice and the students were supposed to choose another response, which happened to be an obvious incorrect choice. Cholesterol certainly has four rings, so what’s the problem?

The day after the exam, students started complaining on the newsgroup. Apparently Prof. X (no, it wasn’t me, this isn’t my course) said in lecture that cholesterol has only three rings and students have the recording to prove it! Several students demanded that they be given a mark for choosing response C. The complaints quickly escalated with some highly indignant students demanding an extra mark on the exam. According to their logic, it is unfair for students to be penalized because the Professor made a mistake in the lecture.

Other students chimed in. They pointed out that the Professor’s notes referred to four rings and the textbook clearly shows four rings; A, B, C, and D. They suggested that their fellow students have a responsibility to study from the notes and textbook as well as the recording. If there was a discrepancy, then it was up to the student to resolve it, including asking the Professor if necessary.

One of the best responses was from student “YYZ,” who has given me permission to quote him.

I have mixed feeling about this. On the one hand, I understand why students would want to take advantage of cheap technology to make a permanent record of my words of wisdom. :-)

On the other hand, my words aren’t always wise and I don’t want students to memorize everything I say without checking it against the textbook and other sources. Lecture recordings should be supplements to learning and not the only source. (Don’t get me started about podcasts!)

This point was brought home in one of the threads on our student forums. The students in one of our biochemistry courses had just finished a midterm exam. One of the multiple choice questions was about cholesterol. For those of you who haven’t committed the structure of cholesterol to memory—I am one—I’m including a picture. The description in the textbook (it happens to be my textbook) is ....

Steroids are a third class of lipids found in the membranes of eukaryotes, and, very rarely, in bacteria. Steroids, along with lipid vitamins and terpenes, are classified as isoprenoids because their structures are related to the five carbon molecule isoprene. Steroids contain four fused rings: three six-carbon rings designated A, B, and C and a five-carbon D ring.

I then go on to describe cholesterol, an important steroid.

I then go on to describe cholesterol, an important steroid.Choice “C” in the multiple choice question referred to the 4-ring structure of cholesterol. It was a correct choice and the students were supposed to choose another response, which happened to be an obvious incorrect choice. Cholesterol certainly has four rings, so what’s the problem?

The day after the exam, students started complaining on the newsgroup. Apparently Prof. X (no, it wasn’t me, this isn’t my course) said in lecture that cholesterol has only three rings and students have the recording to prove it! Several students demanded that they be given a mark for choosing response C. The complaints quickly escalated with some highly indignant students demanding an extra mark on the exam. According to their logic, it is unfair for students to be penalized because the Professor made a mistake in the lecture.

Other students chimed in. They pointed out that the Professor’s notes referred to four rings and the textbook clearly shows four rings; A, B, C, and D. They suggested that their fellow students have a responsibility to study from the notes and textbook as well as the recording. If there was a discrepancy, then it was up to the student to resolve it, including asking the Professor if necessary.

One of the best responses was from student “YYZ,” who has given me permission to quote him.

I’m saying you can’t only listen to the lecture and that’s it. You have to analyze what he says, look at the slides, think over if things make sense, etc. Studying isn’t mindlessly memorizing words coming out of a professors mouth ...By Jove, I think he’s got it! It’s refreshing to see that some students understand how to study and it’s refreshing to see them take on the whiners. That’s how things are going to change in the universities. Professors are the enemy and nothing they say has any credibility (at least in the first two years). Responsible students have to speak up.

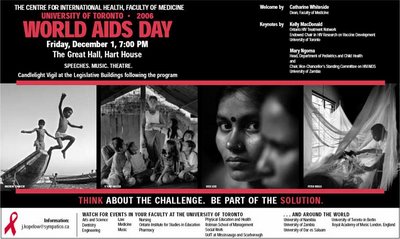

World AIDS Day

The Faculty of Medicine and the University of Toronto are hosting a series of events this week in association with World AIDS Day (Friday, Dec. 1). Check the flyers around the campus for events near you. There will be a student presentation in my class on Wednesday prior to the symposium on Promoting Evidence-based ART in Resource-poor Settings.

Light a Candle

Light a candle and Bristol-Myers Squibb will donate $1, up to a total of $100,000, to the national AIDs fund (USA). I'm usually not a fan of big PHARMA but .... why not?

Monday's Molecule #3

Sunday, November 26, 2006

Imagine No Religion

In The God Delusion, Richard Dawkins refers to John Lennon who asked us to imagine no religion. For those of you who never knew John Lennon, here he is singing Imagine. No, John, you're not the only one. (Thanks to The Scientific Indian for finding the video on Google Videos.)

The Three Domain Hypothesis (part 3)

The scientific dispute over The Three Domain Hypothesis is based on the validity of RNA trees, the importance of protein trees that disagree with the rRNA tree, the evidence for fusions, and the frequency of Lateral Gene Transfer (LGT). But, as usual, there’s more to it than just science. The side with the best advocates has a huge advantage in fights like this.

Let's set the stage by quoting from the article by William Martin.

One of the key problems in deep phylogeny is choosing the right gene. Pace argues in favor of ribosomal RNA—not a surprise since he has invested over 20 years in this molecule. Ideally, what kind of gene do we want to examine in order to determine the deepest branches in the tree of life? According to Pace there are three criteria ....

There’s no question about #1. Ribosomal RNA genes are fond in all species. There are very few other genes that meet this criterion. Almost all other candidates are absent in at least a few species. Ribosomal RNA satisfies #3 as well. Even the small subunit is large enough.

What about #2? Which genes have “resisted” lateral gene transfer? You can’t just declare by fiat that ribosomal RNA genes haven’t been transferred. It’s a debatable question as we’ll see later on.

I would add three other criteria.

Ribosomal RNA does not encode protein. That’s a serious problem that Pace never addresses.

Ribosomal RNA genes are well conserved but not as highly conserved as some others. This is why rRNA can be used to distinguish closely related species whereas the sequences of other genes are identical unless the species diverged more than 10-20 million years ago. Part of the problem with using rRNA sequences in deep phylogeny is that they are too divergent.

Having declared that ribosomal RNA genes are the best choice, Pace then goes on to show us the “true”universal tree of life. As you can see, it is divided into three distinct clusters separated by long branches. The clades represent Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukaryotes; the Three Domains. The prokarotes (Bacteria and Archaea) seem to associate and the eukaryotes seem to be more distantly related.

Having declared that ribosomal RNA genes are the best choice, Pace then goes on to show us the “true”universal tree of life. As you can see, it is divided into three distinct clusters separated by long branches. The clades represent Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukaryotes; the Three Domains. The prokarotes (Bacteria and Archaea) seem to associate and the eukaryotes seem to be more distantly related.

But first impressions can be misleading. Pace puts the root on the branch leading to bacteria and not on the long branch leading to Eukaryotes. This root is based entirely on two old 1989 papers, which he references. Both of these papers have been refuted, but that’s not something you would learn from reading Pace’s article. (There are other, more recent, experiments that root the tree on the bacterial branch and these should have been used. The fact that they weren’t reflects Pace’s degree of critical thinking on this problem. )

To many of us, the large scale structure of the tree of life just doesn’t look right. The long branches leading from the trifurcation point to Bacteria and Eukaryotes smack of artifact. The branching within each of the domains looks too simple. It’s part of the reason why there’s skepticism about the rRNA tree, as we’ll see.

The rest of the article is a passionate defense of the importance of bacteria. I agree with him, for the most part, and so do lots of evolutionary biologists. Bacteria are much more important than eukaryotes! :-)

Pace contributes very little to the debate since he is not willing to entertain any doubts about the Three Domain Hypothesis. For that we have to look at some other papers.

Microbobial Phylogeny and Evolution: Concepts and Controversies Jan Sapp, ed., Oxford University Press, Oxford UK (2005)

Jan Sapp The Bacterium’s Place in Nature

Norman Pace The Large-Scale Structure of the Tree of Life.

Woflgang Ludwig and Karl-Heinz Schleifer The Molecular Phylogeny of Bacteria Based on Conserved Genes.

Carl Woese Evolving Biological Organization.

W. Ford Doolittle If the Tree of Life Fell, Would it Make a Sound?.

William Martin Woe Is the Tree of Life.

Radhey Gupta Molecular Sequences and the Early History of Life.

C. G. Kurland Paradigm Lost.

Let's set the stage by quoting from the article by William Martin.

Thus, it seems to me that there is a schisma abrew in cell evolution, with the rRNA tree and proponents of its infallibility on the one side and other forms of evidence, proponents of LGT, or proponents of a symbiotic origin of eukaryotes on the other. The former camp is well organized behind a unified view (be it right or wrong, still a view) and is arguing that we already have the answers to microbial evolution. The latter camp is not organized into castes of recognized leadership and followers, meaning that (if we are lucky) concepts and their merits, not position or power, will determine the outcome of the battle as to what ideas might or might not be worthwhile entertaining as a working hypothesis for the purpose of further scientific endeavour.The article by Norman Pace represents the side that already has the answers. He is a strong proponent of the Three Domain Hypothesis. These days, the main thrust of his argument is that we should all jump on the bandwagon or risk being left behind. I heard him speak in San Francisco last April and he sounded more like a preacher than a scientist. His article in Nature, ”Time for a Change”, is an example of the way the Three Domain Hypothesis proponents have been arguing for 20 years.

One of the key problems in deep phylogeny is choosing the right gene. Pace argues in favor of ribosomal RNA—not a surprise since he has invested over 20 years in this molecule. Ideally, what kind of gene do we want to examine in order to determine the deepest branches in the tree of life? According to Pace there are three criteria ....

1. The gene must be universal.Only ribosomal RNA meets all three criteria, says Pace.

2. The gene must have resisted lateral gene transfer.

3. The gene must be large enough to provide useful phylogenetic information.

There’s no question about #1. Ribosomal RNA genes are fond in all species. There are very few other genes that meet this criterion. Almost all other candidates are absent in at least a few species. Ribosomal RNA satisfies #3 as well. Even the small subunit is large enough.

What about #2? Which genes have “resisted” lateral gene transfer? You can’t just declare by fiat that ribosomal RNA genes haven’t been transferred. It’s a debatable question as we’ll see later on.

I would add three other criteria.

4. The gene must be unique, or if it isn’t, paralogues must be easily recognized.Ribosomal RNA doesn’t do so well when we add these criteria. Most bacterial genomes have multiple copies of ribosomal RNA genes. They are usually 99% similar but there are known examples of more divergent paralogues. This is not likely to be a serious problem for deep phylogeny, but it has caused problems at the species level.

5. The gene must encode a protein because it’s much more accurate to analyze amino acid sequences than nucleic acid sequences. (And easier to align.)

6. The gene must be highly conserved in order to retain significant sequence similarity at the deepest levels.

Ribosomal RNA does not encode protein. That’s a serious problem that Pace never addresses.

Ribosomal RNA genes are well conserved but not as highly conserved as some others. This is why rRNA can be used to distinguish closely related species whereas the sequences of other genes are identical unless the species diverged more than 10-20 million years ago. Part of the problem with using rRNA sequences in deep phylogeny is that they are too divergent.

Having declared that ribosomal RNA genes are the best choice, Pace then goes on to show us the “true”universal tree of life. As you can see, it is divided into three distinct clusters separated by long branches. The clades represent Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukaryotes; the Three Domains. The prokarotes (Bacteria and Archaea) seem to associate and the eukaryotes seem to be more distantly related.

Having declared that ribosomal RNA genes are the best choice, Pace then goes on to show us the “true”universal tree of life. As you can see, it is divided into three distinct clusters separated by long branches. The clades represent Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukaryotes; the Three Domains. The prokarotes (Bacteria and Archaea) seem to associate and the eukaryotes seem to be more distantly related. But first impressions can be misleading. Pace puts the root on the branch leading to bacteria and not on the long branch leading to Eukaryotes. This root is based entirely on two old 1989 papers, which he references. Both of these papers have been refuted, but that’s not something you would learn from reading Pace’s article. (There are other, more recent, experiments that root the tree on the bacterial branch and these should have been used. The fact that they weren’t reflects Pace’s degree of critical thinking on this problem. )

To many of us, the large scale structure of the tree of life just doesn’t look right. The long branches leading from the trifurcation point to Bacteria and Eukaryotes smack of artifact. The branching within each of the domains looks too simple. It’s part of the reason why there’s skepticism about the rRNA tree, as we’ll see.

The rest of the article is a passionate defense of the importance of bacteria. I agree with him, for the most part, and so do lots of evolutionary biologists. Bacteria are much more important than eukaryotes! :-)

Pace contributes very little to the debate since he is not willing to entertain any doubts about the Three Domain Hypothesis. For that we have to look at some other papers.

Microbobial Phylogeny and Evolution: Concepts and Controversies Jan Sapp, ed., Oxford University Press, Oxford UK (2005)

Jan Sapp The Bacterium’s Place in Nature

Norman Pace The Large-Scale Structure of the Tree of Life.

Woflgang Ludwig and Karl-Heinz Schleifer The Molecular Phylogeny of Bacteria Based on Conserved Genes.

Carl Woese Evolving Biological Organization.

W. Ford Doolittle If the Tree of Life Fell, Would it Make a Sound?.

William Martin Woe Is the Tree of Life.

Radhey Gupta Molecular Sequences and the Early History of Life.

C. G. Kurland Paradigm Lost.

ORFans

Over on talk.origins there's a discussion about ORFans. It was started by referring to an article from The Christian Post that reported on a talk given by Paul Nelson. According to Nelson, the presence of ORFan genes in bacterial genomes represents a serious change to evolution.

Ernest Major posted a nice analysis of the paper with references to the many eplanations of the origin of ORFans. I'd like to add a bit more to his description of the "problem."

Here's the primary reference ...

ORF stands for "open reading frame" a term that refers to a stretch of codons for amino acids. It means that this ORF probably identifies a protein encoding gene. In order to be meaningful, the ORF should; (a) begin with a start codon, (b) end with a termination codon, and (c) contain a minimum number of codons (typically more than 100).

In this age of genomics and bioinformatics, there are computer programs that scan both strands of DNA to identify ORF's. These are putative genes. When the first genomes were sequenced there were a lot of putative genes that matched sequences already in the database. In other words, the computer programs identified ORF's that showed significant sequence similarity to individual genes that had already been cloned and sequenced by other labs. These genomic ORF's represented genes that were homologous to known genes.

Yin and Fischer are interested in the ORF's that aren't homologous to known genes. They concentrate on bacterial (prokaryote) genomes since the coverage is more extensive. As more and more genomes were sequenced the number of new genes represented by these non-homologous ORF's declined, as expected. Today, for every new genome that's added to the database, almost 80% of the genes have been previously identified.

The surprise is that there are so many unique ORF's in every genome. These are putative genes that have no known homologues. They are ORFans. In order to determine the number of ORFans, Yin and Fischer analyzed the complete genomes of 277 bacteria. For each and every gene they ran a search against all other genes in the database. The result was the histogram shown below.

The figure shows the distribution of all 818,906 ORF's in 277 sequenced prokaryote genomes. (A typical genome has about 3000 genes.) The bottom axis represents the frequency of each of the putative genes in the database. The tall bar at the extreme left-hand side shows the number of ORF's that are only found in a single species. These are the ORFans. There are almost 80,000 of them; or, about 280 per genome. This is what the paper is all about.

The figure shows the distribution of all 818,906 ORF's in 277 sequenced prokaryote genomes. (A typical genome has about 3000 genes.) The bottom axis represents the frequency of each of the putative genes in the database. The tall bar at the extreme left-hand side shows the number of ORF's that are only found in a single species. These are the ORFans. There are almost 80,000 of them; or, about 280 per genome. This is what the paper is all about.

There are some putative genes that are only present in one or two related species. These are represented by the bars at U=0.01, 0.02 etc. Some of these are also counted as ORFans since they are only present in closely related species.

As you can see, there's a broad peak of genes found in about 60% (U=0.6) of all sequenced prokaryote genomes. These represent the standard genes of metabolism. Hardly any genes are present in every single species (U=1.0). This is because the database may be incomplete, the genes may have diverged too far to be detectable, or the species is really missing that gene.

Where did the unique genes (ORFans) come from? If they are real, it seems unlikely that they sprung into existence in a single lineage. They were most likely "borrowed" from a distantly related species by a process known as lateral gene transfer. However, as more and more genomes from diverse species are added to the database it becomes worrisome that the source of these genes isn't identified.

What about viruses? It has long been known that viral genes can be incorporated into bacterial genomes so this seems like a good possibility. Yin and Fischer screened all 818,906 ORF's against the viral database to test this hypothesis. They found that only 2.8% of bacterial ORFans have detectable homologues in the viral genomes. Thus, the transfer of viral genes to bacterial genomes doesn't seem to account for all of the ORFans.

The authors discuss the problems with their experiment and urge us not to reject the viral origin hypothesis just yet. There are only 280 bacteriophage in the viral genome databse and this represents a very tiny percentage of all bacteriophage. (There may be 100 million different phage.) There are still lots of places for ORFan homologues to hide.

I think there's another problem; one that the authors are not taking seriously. It's quite possible that many of the ORFans aren't real genes at all. The computer programs that detect these ORF's are notorious for their false positives. There may be ORFan "genes" that are never transcribed or there may be ORFan "genes" that are transcribed and translated but the protein product doesn't do anything. It's an accident of evolution. In addressing this problem the authors make the common mistake of pointing to those cases where known ORFans have proven to be functional genes, while ingoring that fact most haven't. Just because some of them are real genes doesn't mean that all of them are. If most ORFans are artifacts then it's not surprising that they aren't found in other species.

Ernest Major posted a nice analysis of the paper with references to the many eplanations of the origin of ORFans. I'd like to add a bit more to his description of the "problem."

Here's the primary reference ...

Yin, Y. and Fischer, D. (2006) On the origin of microbial ORFans: quantifying the strength of the evidence for viral lateral transfer. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2006, 6:63

[Get your free copy here]Open Access Charter

ORF stands for "open reading frame" a term that refers to a stretch of codons for amino acids. It means that this ORF probably identifies a protein encoding gene. In order to be meaningful, the ORF should; (a) begin with a start codon, (b) end with a termination codon, and (c) contain a minimum number of codons (typically more than 100).

In this age of genomics and bioinformatics, there are computer programs that scan both strands of DNA to identify ORF's. These are putative genes. When the first genomes were sequenced there were a lot of putative genes that matched sequences already in the database. In other words, the computer programs identified ORF's that showed significant sequence similarity to individual genes that had already been cloned and sequenced by other labs. These genomic ORF's represented genes that were homologous to known genes.

Yin and Fischer are interested in the ORF's that aren't homologous to known genes. They concentrate on bacterial (prokaryote) genomes since the coverage is more extensive. As more and more genomes were sequenced the number of new genes represented by these non-homologous ORF's declined, as expected. Today, for every new genome that's added to the database, almost 80% of the genes have been previously identified.

The surprise is that there are so many unique ORF's in every genome. These are putative genes that have no known homologues. They are ORFans. In order to determine the number of ORFans, Yin and Fischer analyzed the complete genomes of 277 bacteria. For each and every gene they ran a search against all other genes in the database. The result was the histogram shown below.

The figure shows the distribution of all 818,906 ORF's in 277 sequenced prokaryote genomes. (A typical genome has about 3000 genes.) The bottom axis represents the frequency of each of the putative genes in the database. The tall bar at the extreme left-hand side shows the number of ORF's that are only found in a single species. These are the ORFans. There are almost 80,000 of them; or, about 280 per genome. This is what the paper is all about.

The figure shows the distribution of all 818,906 ORF's in 277 sequenced prokaryote genomes. (A typical genome has about 3000 genes.) The bottom axis represents the frequency of each of the putative genes in the database. The tall bar at the extreme left-hand side shows the number of ORF's that are only found in a single species. These are the ORFans. There are almost 80,000 of them; or, about 280 per genome. This is what the paper is all about.There are some putative genes that are only present in one or two related species. These are represented by the bars at U=0.01, 0.02 etc. Some of these are also counted as ORFans since they are only present in closely related species.

As you can see, there's a broad peak of genes found in about 60% (U=0.6) of all sequenced prokaryote genomes. These represent the standard genes of metabolism. Hardly any genes are present in every single species (U=1.0). This is because the database may be incomplete, the genes may have diverged too far to be detectable, or the species is really missing that gene.

Where did the unique genes (ORFans) come from? If they are real, it seems unlikely that they sprung into existence in a single lineage. They were most likely "borrowed" from a distantly related species by a process known as lateral gene transfer. However, as more and more genomes from diverse species are added to the database it becomes worrisome that the source of these genes isn't identified.

What about viruses? It has long been known that viral genes can be incorporated into bacterial genomes so this seems like a good possibility. Yin and Fischer screened all 818,906 ORF's against the viral database to test this hypothesis. They found that only 2.8% of bacterial ORFans have detectable homologues in the viral genomes. Thus, the transfer of viral genes to bacterial genomes doesn't seem to account for all of the ORFans.

The authors discuss the problems with their experiment and urge us not to reject the viral origin hypothesis just yet. There are only 280 bacteriophage in the viral genome databse and this represents a very tiny percentage of all bacteriophage. (There may be 100 million different phage.) There are still lots of places for ORFan homologues to hide.

I think there's another problem; one that the authors are not taking seriously. It's quite possible that many of the ORFans aren't real genes at all. The computer programs that detect these ORF's are notorious for their false positives. There may be ORFan "genes" that are never transcribed or there may be ORFan "genes" that are transcribed and translated but the protein product doesn't do anything. It's an accident of evolution. In addressing this problem the authors make the common mistake of pointing to those cases where known ORFans have proven to be functional genes, while ingoring that fact most haven't. Just because some of them are real genes doesn't mean that all of them are. If most ORFans are artifacts then it's not surprising that they aren't found in other species.

Saturday, November 25, 2006

A Teapot in Space

Freecell

Andrew Brown over at Helmintholog points us to Freecell fanatic about a man who has played all 32,000 games three times, and is working his way through the fourth round. You probably don't want to know which games can be won by never using the free cells, but I bet you want to know the one and only game that can't be won at all!

Andrew Brown over at Helmintholog points us to Freecell fanatic about a man who has played all 32,000 games three times, and is working his way through the fourth round. You probably don't want to know which games can be won by never using the free cells, but I bet you want to know the one and only game that can't be won at all! Here it is!!!

Dissection of larval CNS in Drosophila melanogaster

Have you ever wanted to know how to remove the central nervous system (CNS) from a fruit fly larva? Of course you have.

Now you can see an expert in action thanks to The Journal of Visualized Experiments. Nathaniel Hafer in Paul Schedl's lab at Princeton shows you how to do it.

Watch the CNS form during development of the embryo in this video from YouTube. (The CNS is the black thing at the bottom.)

Now you can see an expert in action thanks to The Journal of Visualized Experiments. Nathaniel Hafer in Paul Schedl's lab at Princeton shows you how to do it.

Watch the CNS form during development of the embryo in this video from YouTube. (The CNS is the black thing at the bottom.)

Calico Cats

There's been a discussion on talk.origins about calico cats—do they have to be female? The color pattern is an interesting combination of sex-linked genetics and epigenetics. Epigenetics is the inheritance of characteristics other than nuleotide sequence. In this case, it's inheritance of an inactivated X-chromosome.

There's been a discussion on talk.origins about calico cats—do they have to be female? The color pattern is an interesting combination of sex-linked genetics and epigenetics. Epigenetics is the inheritance of characteristics other than nuleotide sequence. In this case, it's inheritance of an inactivated X-chromosome.I used calico cats as an example in the Moran/Scrimgeour et al. textbook (1994) published by Neil Patterson/Prentice Hall. Here's an excerpt from that book.

One X Chromosome Is Inactivated in Mammalian Females by Condensation into Heterochromatin

The DNA within polytene chromosome bands is condensed but nevertheless accessible to transcription factors. However, there are forms of chromatin known as heterochromatin, that are much more highly condensed. Constitutive heterochromatin refers to chromosomes or parts of chromosomes that are heterochromatic in all cells of a given species. Examples of constitutive heterochromatin can be found in every multicellular eukaryote and can take the form of entire chromosomes or parts of chromosomes. For example, some maize cells contain multiple copies of a small, heterochromatic chromosome called chromosome B. In addition, between one-fourth and one-third of all DNA in Drosophila is found in heterochromatic regions near the centromeres.

Condensation of chromatin is an effective mechanism of repressing eukaryotic gene expression and is best exemplified by the process of X-chromosome inactivation in mammalian females. The sex of a mammal is determined by the presence or absence of the male-specific Y chromosome. In humans, males normally have one X and one Y chromosome per somatic cell, whereas females normally have two X chromosomes per somatic cell. The X chromosome is quite large and contains a number of genes, most of which play no role in sex differences. Proper human development requires that only one X chromosome be fully active in each somatic cell of an adult. Thus, one of the X chromosomes in females is inactivated by condensation into heterochromatin (Figure 27.53). Such condensed chromosomes are knwon as sex-chromosome bodies or Barr bodies. X-chromosome inactivation is one example of the genetic phenomenon known as dosage compensation because it involves regulating the dosage of genes.

In human females, X-chromsome inactivation occurs very early in embryonic development, at about the 20-cell stage. Condensation of an X chromosome into heterochromatin appears to begin at a unique point, the xist gene, and proceed bidirectionally along the DNA. Inactivation is associated with extensive methylation of DNA. Once a specific X chromosome has been inactivated in a particular cell of the 20-cell embryo, the same X chromosome remains inactivated in all daughter cells descended from that presursor cell (Figure 27_54). In each human cell, either the maternal of paternal X chromosome can be inactivated.

The frequencies of maternal and paternal X chromosome inactivation vary among mammals. In female marsupials, for example, the paternal X chromosome appears to be preferentially inactivated. This observation indicates that the maternal and paternal chromosomes are not identical and can be distinguished in the developing embryo. However, in most other mammals, including humans, the X chromosome that is condensed appears to be selected more or less at random. As a result, some of the cells in the mature organism contain an active maternal X chromsome, and some contain an active paternal chromosome. Consequently, the organism is a mosaic composed of cells expressing different genetic information.

Sometime cells containing an active maternal X chromosome can be physically distinguished from those containing an active paternal X chromosome. An example of such a visible mosaic is the calico cat, which has patches of orange and black fur. Calico cats are always female if they have normal X chromosomes. The patchiness results from random inactivation of X chromosomes in female cats in which the X chromosome inherited from one parent carries the gene [allele] for orange fur and the X chromosome inherited from the other parent carries the gene [allele] for black fur. (The white fur on the underside is due to expression of an autosomal gene.)

Genetic mosaicism due to X-chromosome inactivation also occurs in human females. For example, the gene for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenease is located on the X chromosome. If each chromosome carries a different allele, patches of cells will contain either one isoform or the other, depending on which X chromosome is inactivated. The theory of X-chromosome inactivation was developed in large part by Mary Lyon, and the process is sometimes known as Lyonization.

[Calico_cat_Phoebe is from Free Software Foundation.]

Go, Leafs, Go!!!

Tonight is hockey night in Canada. We get to watch Don Cherry on TV.

Tonight is hockey night in Canada. We get to watch Don Cherry on TV.Last night, the Leafs punished the Washington Capitals 7-1. This puts them solidly in third place in the Northeast Division of the Eastern Conference. They're only 8 points behind the division leader (Buffalo) with over 55 games left!

Tonight, the Leafs play Boston at the Air Canada Centre. Some of you might recall that Boston barely squeaked out an overtime victory last time they played. Boston is home to Boston University, MIT, and some other schools.

Tonight, the Leafs play Boston at the Air Canada Centre. Some of you might recall that Boston barely squeaked out an overtime victory last time they played. Boston is home to Boston University, MIT, and some other schools.This is the year the Leafs are going to win the Stanley Cup. Yes Siree, Bob, you can count on it! There'll be dancing in the streets next June.

Poking with Needles, Running with Scissors

noctiluca has posted an interesting article on talk.origins, "The Humpty Dumpty argument - the wit and wisdom of Jonathan Wells." noctiluca quotes Jonathan Wells from a Lee Strobel DVD called"The Case for the Creator." (If you go to the site you can actually watch clips showing the IDiots in action!)

The talk.origins article closes with, "My wife didn't know if I was laughing or crying." Thanks noctilura, for sharing that with us. :-)

We tell little children not to run with scissors. We should not forget to warn them against poking at things with needles.

It comes down to this: no matter how many molecules you can produce with early earth conditions, plausible conditions, you're still nowhere near producing a living cell.You can't make this stuff up. And you wonder why we call them IDiots?

And here's how I know: If I take a sterile test tube and I put in it a little bit of fluid with just the right salts, just the right balance of acidity and alkalinity, just the right temperature - the perfect solution for a living cell, and I put in it one living cell, this cell is alive, it has everything it needs for life. Now I take a sterile needle and I poke that cell, and all its stuff leaks out into this test tube, you have in this nice little test tube all the molecules you need for a living cell, not just the pieces of the molecules but the molecules themselves, and you can't make a living cell out of them.

You can't put Humpty Dumpty back together again. So what makes you think that a few amino acids dissolved in the ocean are going to give you a living cell? It's totally unrealistic.

The talk.origins article closes with, "My wife didn't know if I was laughing or crying." Thanks noctilura, for sharing that with us. :-)

We tell little children not to run with scissors. We should not forget to warn them against poking at things with needles.

Friday, November 24, 2006

Biochemistry Major

How many universities have a biochemistry major? My students want to know if most universites have such a program. We know that it's common in Canadian universities. What about the rest of the world?

Teaching the Science of Evolution under the Threat of Alternative Views

I posted a version of this over at Stranger Fruit but after doing so I thought it might be of interest to others ...

After years of keeping quiet, I was prompted to enter this debate after attending a meeting organized by the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology [ASBMB]. The title of the symposium was "Teaching the Science of Evolution under the Threat of Alternative Views". You can see the video by following the link.

Now, it seemed to me entirely inappropriate to emphasize Miller's religion when introducing him at a scientific conference. It seemed inappropriate to invite Rev. Ted Peters to give one of the talks. It seemed inappropriate for Eugenie Scott to praise Miller but take a swipe at Dawkins.

For me that was the tipping point. Now, I know it sounds childish to say "they started it" but it's important to keep it in mind. Atheists have kept their mouths shut for years but the attack on atheistic views—and the praise of religious scientists—have escalated in recent years.

I was getting tired of being told that atheists were not welcome but religious scientists were.

The important talk is the one by Rev. Ted Peters, an ordained pastor of the Evangelical Lutheran church. He makes the case for Theistic Evolution. Keep in mind that this talk was given at a scientific meeting and most of the audience were scientists. A good many of them were atheists.

Listen to Eugenie Scott's talk as well. I like the bit about "We are not Darwinists." At the end of her talk she presents the case for appeasement: Dawkins bad, Peters good.

After years of keeping quiet, I was prompted to enter this debate after attending a meeting organized by the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology [ASBMB]. The title of the symposium was "Teaching the Science of Evolution under the Threat of Alternative Views". You can see the video by following the link.

Now, it seemed to me entirely inappropriate to emphasize Miller's religion when introducing him at a scientific conference. It seemed inappropriate to invite Rev. Ted Peters to give one of the talks. It seemed inappropriate for Eugenie Scott to praise Miller but take a swipe at Dawkins.

For me that was the tipping point. Now, I know it sounds childish to say "they started it" but it's important to keep it in mind. Atheists have kept their mouths shut for years but the attack on atheistic views—and the praise of religious scientists—have escalated in recent years.

I was getting tired of being told that atheists were not welcome but religious scientists were.

The important talk is the one by Rev. Ted Peters, an ordained pastor of the Evangelical Lutheran church. He makes the case for Theistic Evolution. Keep in mind that this talk was given at a scientific meeting and most of the audience were scientists. A good many of them were atheists.

Listen to Eugenie Scott's talk as well. I like the bit about "We are not Darwinists." At the end of her talk she presents the case for appeasement: Dawkins bad, Peters good.

Undefended Borders

Mythbusters

The New York Times asks whether Mythbusters is The Best Science Show on Television. Who cares? It's lots of fun even if it doesn't teach very much science. Gets my vote.

Thursday, November 23, 2006

The Neville Chamberlain School of Evolutionists

Richard Dawkins writes about the "Neville Chamberlain 'appeasement' school" of evolutionists. These are scientists who are willing to compromise science in order to form an alliance with some religious groups who oppose Christian fundamentalism. Do you believe in miracles? That's okay, it's part of science. Do you believe that God guides evolution in order to produce beings who worship him? That's fine too; it's all part of the Neville Chamberlain version of intelligent design. Souls, moral law, life after death, a fine-tuned universe, angels, the efficacy of prayer, transubstantiation ... all these things are part of the new age science according to the appeasement school. There's no conflict with real science. We mustn't question these things for fear of alienating our potential allies in the fight against the IDiots. Welcome to the big tent.

Ed Brayton has declared himself one of the leading members of the Neville Chamberlain School. And now, John Lynch and Pat Hayes have joined the Ed Brayton team.

Me and PZ are on the side of science and rationalism.

Young Earth Creationsts (YEC's) and Intelligent Design Creationists (IDiots) are anti-science because they propose explanations of the natural world that conflict with science. But they're not alone in doing that. Many of the so-called Theistic Evolutionists also promote a version of evolution that Darwin wouldn't recognize. They are more "theist" than "evolutionist."

For some reason the Neville Chamberlain team is willing to attack the bad science of a Michael Denton or a Michael Behe but not the equally—and mostly indistinguishable—bad science of leading Theistic Evolutionists. Isn't that strange?

Public understanding of science will not be advanced by people like Francis Collins, Simon Conway Morris, and Ken Miller. They are subverting science in order to make it conform to their personal religious beliefs. (Which, by the way, conflict.) They are doing more harm to science than those who oppose it directly from the outside because the Theistic Evolutionists are subverting from within. It is sad that they are being supported by people who should know the difference between rationalism and superstition.

Is the appeasement strategy working? Of course not, but the most amazing thing is happening. The Neville Chamberlain School thinks it is winning in spite of the fact that leading politicians oppose evolution; most schools don't teach evolution; and the general public doesn't accept evolution. Talk about delusion. The appeasers think we should continue down the same path that led us to this situation. They think we should continue to compromise science in order to accommodate the religious moderates.

PZ Myers is only the most recent in a long list of people who have noticed that the good guys are not winning ...

Ed Brayton has declared himself one of the leading members of the Neville Chamberlain School. And now, John Lynch and Pat Hayes have joined the Ed Brayton team.

Me and PZ are on the side of science and rationalism.

Young Earth Creationsts (YEC's) and Intelligent Design Creationists (IDiots) are anti-science because they propose explanations of the natural world that conflict with science. But they're not alone in doing that. Many of the so-called Theistic Evolutionists also promote a version of evolution that Darwin wouldn't recognize. They are more "theist" than "evolutionist."

For some reason the Neville Chamberlain team is willing to attack the bad science of a Michael Denton or a Michael Behe but not the equally—and mostly indistinguishable—bad science of leading Theistic Evolutionists. Isn't that strange?

Public understanding of science will not be advanced by people like Francis Collins, Simon Conway Morris, and Ken Miller. They are subverting science in order to make it conform to their personal religious beliefs. (Which, by the way, conflict.) They are doing more harm to science than those who oppose it directly from the outside because the Theistic Evolutionists are subverting from within. It is sad that they are being supported by people who should know the difference between rationalism and superstition.

Is the appeasement strategy working? Of course not, but the most amazing thing is happening. The Neville Chamberlain School thinks it is winning in spite of the fact that leading politicians oppose evolution; most schools don't teach evolution; and the general public doesn't accept evolution. Talk about delusion. The appeasers think we should continue down the same path that led us to this situation. They think we should continue to compromise science in order to accommodate the religious moderates.

PZ Myers is only the most recent in a long list of people who have noticed that the good guys are not winning ...

Now, what is this winning strategy that Ed's Team is pushing? It seems to be more of the same, the stuff that we've been doing for 80 years, accommodating the watering down of science teaching to avoid conflict with religious superstition…the strategy that has led to a United States where a slim majority opposes the idea of evolution, and we're left with nothing but a struggle in the courts to maintain the status quo.Hallelujah! Right on, brother.

I don't know why this is so hard to understand. We are not winning. We are clinging to tactics that rely on legal fiat to keep nonsense out of the science classroom, while a rising tide of uninformed, idiotic anti-science opinion, tugged upwards by fundamentalist religious fervor, cripples science education. Treading water is not a winning strategy. I'm glad we're not sinking, and I applaud the deserving legal efforts that have kept us afloat, but come on, people, this isn't winning.

Peer Marking

Today's Toronto Star has an interesting article on Peer Marking Gets a Negative Grade.

Students in one of our first year psychology classes were asked to submit a short writing assignment to an online evaluation program called "peerScholar." The site, which was developed by teachers at our Scarborough campus, is set up to allow papers to be graded anonomously by fellow students.

University of Toronto Teaching Assistants, represented by their union (CUPE local 3902), objected. They say this is a blatent attempt to do away with TA's in favor of a computer program. The students in the class also expressed some concern, according to the newspaper article. Apparently, students see the peer evaluation system as "inaccurate" and "unfair."

I first heard about this experiment last year when I went to a presentation by one of the authors. What impressed me was the possibility of teaching students how to critically evaluate the work of their fellow students. I was also interested in giving students some direct experience in how their grades are determined. There's no better way to learn how the system works than grading a fellow student. We did it when I was in school. As a matter of fact, I took a university course where our entire grade was based on a group discussion at the end of term where we assigned grades for each other, by consensus. But that was the 60's.

The peerScholar project seemed like a good way of introducing more participation into a course and I was/am seriously thinking of using it in my course. Here's a desrciption of how it works in the PSYA01 class. There's more information on the peerScholar discussion page. I think it's unifortunate that the authors put so much emphasis on saving money by avoiding TA's. While I recognize that's a legitimate concern, I think that peer evaluation is an important goal by itself.

I've seen the data on fairness and accuracy and it's very impressive. Students tend to be a little too hard on their colleagues but that's easy to compensate for. By the second evaluation they've become much better. If the practice were more common, the students would get much better at it. As it is, the grade assigned by the students is at least as good as that assigned by a TA. It tends to deviate more from the grade assigned by the Professors, but then so do the TA's grades.

Students in one of our first year psychology classes were asked to submit a short writing assignment to an online evaluation program called "peerScholar." The site, which was developed by teachers at our Scarborough campus, is set up to allow papers to be graded anonomously by fellow students.

University of Toronto Teaching Assistants, represented by their union (CUPE local 3902), objected. They say this is a blatent attempt to do away with TA's in favor of a computer program. The students in the class also expressed some concern, according to the newspaper article. Apparently, students see the peer evaluation system as "inaccurate" and "unfair."

I first heard about this experiment last year when I went to a presentation by one of the authors. What impressed me was the possibility of teaching students how to critically evaluate the work of their fellow students. I was also interested in giving students some direct experience in how their grades are determined. There's no better way to learn how the system works than grading a fellow student. We did it when I was in school. As a matter of fact, I took a university course where our entire grade was based on a group discussion at the end of term where we assigned grades for each other, by consensus. But that was the 60's.

The peerScholar project seemed like a good way of introducing more participation into a course and I was/am seriously thinking of using it in my course. Here's a desrciption of how it works in the PSYA01 class. There's more information on the peerScholar discussion page. I think it's unifortunate that the authors put so much emphasis on saving money by avoiding TA's. While I recognize that's a legitimate concern, I think that peer evaluation is an important goal by itself.

I've seen the data on fairness and accuracy and it's very impressive. Students tend to be a little too hard on their colleagues but that's easy to compensate for. By the second evaluation they've become much better. If the practice were more common, the students would get much better at it. As it is, the grade assigned by the students is at least as good as that assigned by a TA. It tends to deviate more from the grade assigned by the Professors, but then so do the TA's grades.

Bill Dembski Needs Help, Again

Bill Dembski asks, ...

I don't know how many times we've explained to Bill that not all evolutionary biologists are "Darwinists." I know I first told him four years ago but I'm sure there were others before me. He seems to be a very slow learner.

One of these years he'll realize that there's more to evolution than just natural selection.

I suspect that the “junk DNA” hypothesis was originally made on explicitly Darwinian grounds. Can someone provide chapter and verse? Clearly, in the absence of the Darwinian interpretation, the default assumption would have been that repetitive nucleotide sequences must have some unknown function.Fortunately, there are some smart people who post comments on Uncommon Descent. They have told Bill that the concept of junk DNA is explicitly non-Darwinian. It was proposed by scientists who didn't feel the need to explain everything as an adaptation.

I don't know how many times we've explained to Bill that not all evolutionary biologists are "Darwinists." I know I first told him four years ago but I'm sure there were others before me. He seems to be a very slow learner.

One of these years he'll realize that there's more to evolution than just natural selection.

Iraqi Children Throwing Rocks

This video from YouTube is poignant in so many ways ... It's the same situation that Canadian forces face in Afghanistan. If the children hate us then why are we there?

A Simple Act of Kindness

This morning I drove over to my local Tim Horton's to get a coffee. There was a lineup in the drive-through, as usual. The woman in front of me stopped by the garbage bin and tossed out an empty cup. She missed, and the cup bounced off the receptacle and rolled under her car. She opened the door a crack, peered out, saw nothing, and drove on.

I have to admit I'm really annoyed at this kind of behavior. I hate it when people throw garbage on the street, especially when there are garbage bins everywhere. I've been known to pick up litter and hand it back to the owner. Rather than drive over her discarded cup, I stopped, picked it up, and put it in the bin. I was not thinking nice thoughts when I did this and I made sure that she saw me do it.

Back in the car, I drove up to the window to get my coffee. Imagine my surprise when the server told me my coffee was free today! She informed me that the woman ahead of me had paid for my coffee.

Thanks, whoever you are. You made my day. In fact, you made my week.

I have to admit I'm really annoyed at this kind of behavior. I hate it when people throw garbage on the street, especially when there are garbage bins everywhere. I've been known to pick up litter and hand it back to the owner. Rather than drive over her discarded cup, I stopped, picked it up, and put it in the bin. I was not thinking nice thoughts when I did this and I made sure that she saw me do it.

Back in the car, I drove up to the window to get my coffee. Imagine my surprise when the server told me my coffee was free today! She informed me that the woman ahead of me had paid for my coffee.

Thanks, whoever you are. You made my day. In fact, you made my week.

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

Ten Worst Science Books

John Horgan has upped the ante with his Ten Worst Science Books. I haven't read most of the ones on his list but I certainly agree with Consilience. I disagree with The Tipping Point 'cause it's not a science book and I disagree with Rock of Ages 'cause when you read it carefully you see that Gould has a valid point.

PZ Meiers adds Darwin's Black Box by Michael Behe and The Language of God by Francis Collins. I'm not sure if the Collins book qualifies as science. It's in the superstition section of my local bookstore.

John Lynch over at Stranger Fruit has an even more interesting suggestion for John Horgan's list of worst science books. Lynch would add The End of Science by John Horgan. Ouch!

I have three suggestions. The one everyone is forgetting is Icons of Evolution by Jonathan Wells. This one's a no-brainer.

One of my personal favorites is Sudden Origins: Fossils, Genes, and the Emergence of Species by Jeffrey H. Schwartz. This is a really, really, bad science book.

Another book that gets my vote is Darwin's Dangerous Idea by Daniel Dennett.

PZ Meiers adds Darwin's Black Box by Michael Behe and The Language of God by Francis Collins. I'm not sure if the Collins book qualifies as science. It's in the superstition section of my local bookstore.

John Lynch over at Stranger Fruit has an even more interesting suggestion for John Horgan's list of worst science books. Lynch would add The End of Science by John Horgan. Ouch!

I have three suggestions. The one everyone is forgetting is Icons of Evolution by Jonathan Wells. This one's a no-brainer.

One of my personal favorites is Sudden Origins: Fossils, Genes, and the Emergence of Species by Jeffrey H. Schwartz. This is a really, really, bad science book.

Another book that gets my vote is Darwin's Dangerous Idea by Daniel Dennett.

The Three Domain Hypothesis (part 2)

Jan Sapp sets the tone by outlining the history of bacterial classification and phylogenetic analysis. We’re mostly concerned with the fourth era—the one that begins in the 1990's with the publication of the first bacterial genomes.

I’m not interested in that debate. If the gene trees say that archaebacteria form a separate domain then that’s good enough for me no matter how much they resemble other prokaryotes. Woese (1998) has published an adequate reply to Mayr.

The real arguments are based on conflicting gene trees and the increasingly obvious similarity between bacteria and archaebacteria at the molecular level. How do we resolve the conflicts between the ribosomal RNA trees and examples of equally well-supported trees from proteins? The first thing that comes to mind is that some of the gene phylogenies are just wrong. They are artifacts of some sort and don’t really represent the history of the genes. Most of the debate on this topic concerns the validity of the SSU trees since they are based on nucleotide sequences. It’s well-known that ribosomal RNA trees are prone to long branch attraction artifacts to a greater extend than trees based on amino acid sequences. It’s also well-known that there are some famous mistakes in rRNA trees.

For the time being, let’s assume that all genes trees are accurate representations of the gene history, bearing in mind that the opponents of the Three Domain Hypothesis are not prepared to concede that point.

Conflicting gene trees then have to be artifacts of a different sort. Some of them will accurately represent the evolution of the species while others will not. The ones that don’t follow the phylogeny of the species will deviate because the genes have a different history. Either they have been transferred singly from one species to another or they have been transferred en masse by some sort of fusion event. Sapp discusses both these possibilities.